TransCanada Power Corridor:

A National Grid Uniting Canada

SPECIAL REPORT

NOVEMBER 20, 2025

Generation

The approach presented here to address the implementation challenge of rapidly expanding electricity generation capacity is to build on existing utility plans and projects, both approved and in development, and to close remaining gaps through commercially available technologies within the 2025–2035 timeframe. For 2035 and beyond, new concepts, technologies and innovations for potential integration within the changing supply-mix are described below.

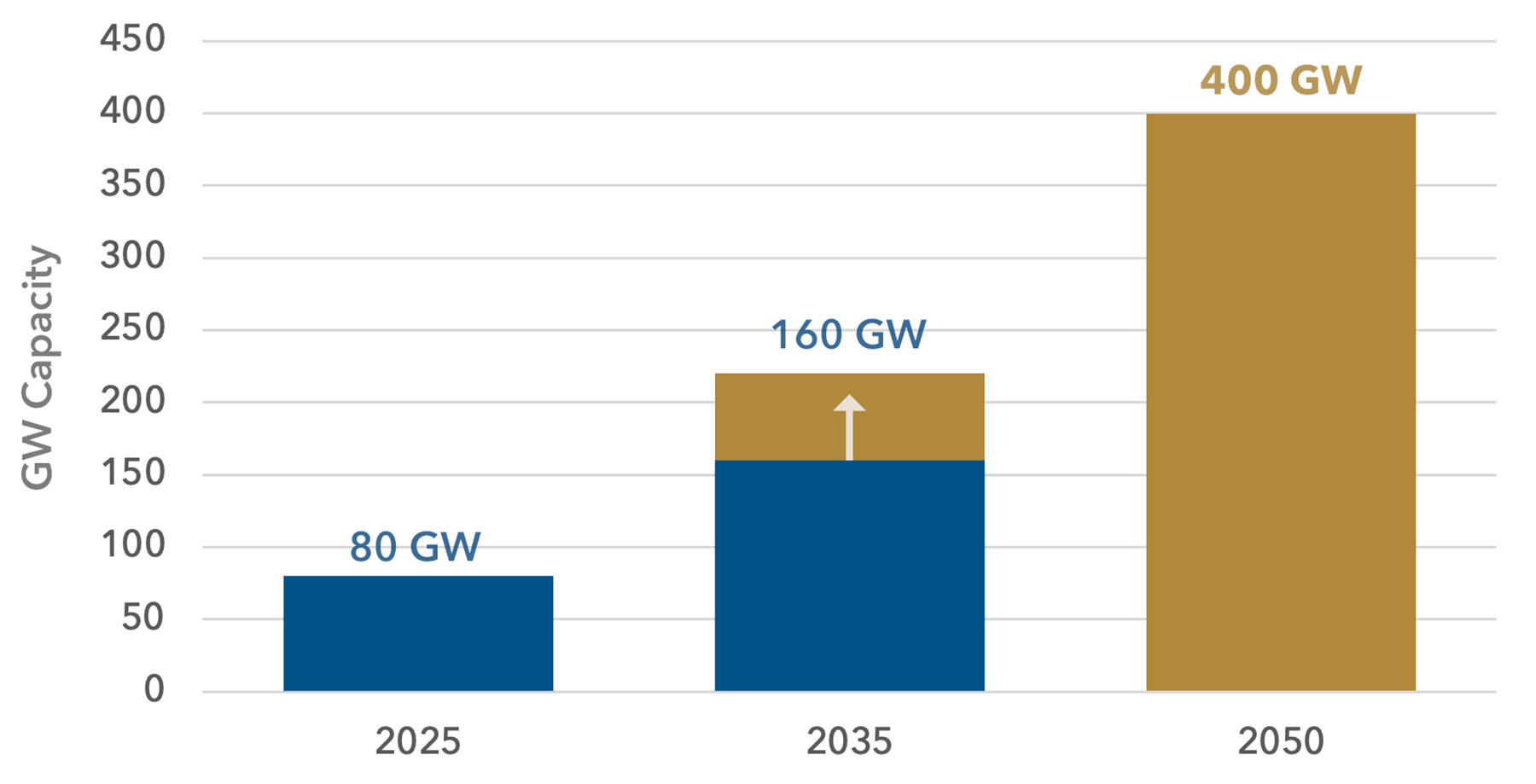

Figure 25 below shows the gap emerging for system capacity additions required beyond existing plans if the share of electricity in final energy consumption increases from the current 23 percent to 50 percent in 2040 and 80 percent in 2050.

Figure 25: Planned vs. Visionary Electricity Capacity Expansion in Canada 2025, 2040, 2060

Source: Authors.

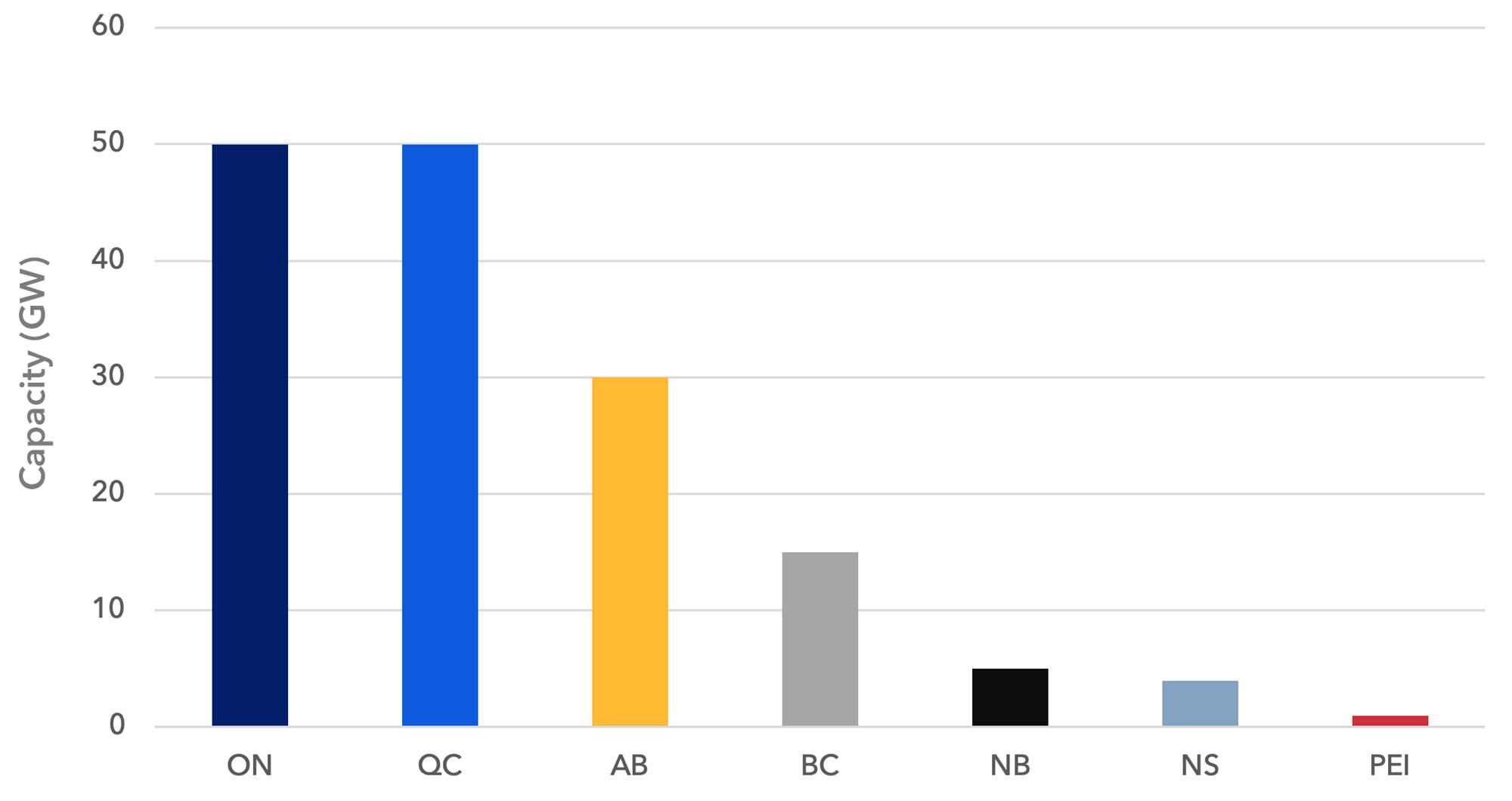

The chart below (Figure 26) shows the cumulative national capacity envisaged by system planners in 2025. These plans are based on economic and energy demand forecasts over the next 20 years, with new system capacity to be built as some of the existing assets come to their useful end-of-life and to accommodate new growth in demand.

Figure 26: Existing Planned System Expansion Capacity (by Province)

Source: Authors.

Table 2: Indicative Requirement of Installed Capacity for Each Energy Resource and Generation Potential the Resource Can Deliver to the Grid (TWh)

| Energy Source | Capacity Factor | Installed Capacity (GW) | Generation Potential (TWh) |

| Nuclear | 90% | ~300 GW | 2400 |

| Hydro | 60% | ~500 GW | 2600 |

| Wind (onshore) | 40% | ~700 GW | 2500 |

| Solar PV | 20% | ~1,500 GW | 2600 |

| Natural Gas - Peaking - Baseload |

30% 85% |

~300GW ~300GW |

800 2,200 |

Source: Authors.

As is shown in Figure 25, a fivefold increase in the installed system capacity by 2050 would be necessary to achieve an 80 percent share of electricity in final energy consumption. Table 2 above illustrates the capacity factors of different energy resources and the expected energy generation potential from each of the options. It should be noted that the generation potential is more than adequate to meet the demand, and an optimal mix of supply resources can be developed that meets the national requirements.

The task for system planners is to optimize across the available primary resources and develop a supply-mix that delivers electricity services reliably and meets the test of affordability. The strengths and limitations of each technology, in addition to the social and environmental acceptability and land use considerations associated with each energy option, would be integrated into an operational plan.

Meeting the demand growth for electricity requires a bold vision and a commitment to large-scale investment in a diverse portfolio of generation technologies. A seamless integration of transmission with generation resources available across the entire Canadian landscape enhances the value of different sources from each province, compensating for the technical limitations and operational attributes of each technology.

For example, the intermittent nature of wind and solar can be accommodated through the installation of large-scale storage facilities (batteries or pumped hydro). The limitations of load following characteristics of nuclear power can be compensated by the “smart” use of natural gas as peaking plants, or low outputs from hydro generation during droughts can be managed through capacity transfers across interprovincial boundaries.

The national grid (described in the section “Transmission” above) not only becomes a symbol of a unifying political force but will allow for the optimization of energy resources across the country, providing low-cost affordable electricity services reliably to homes, businesses and industry.

A low-carbon electricity ecosystem will remain at the core of the transition.

Generation: Building on Existing Strengths

Canada is in an enviable position with an existing low-carbon-intensity power system (see Figure 6a and 6b). The profiles for Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia show a larger role for fossil fuels in the existing system. For the period 2025–2035, the most effective pathway for implementation is to build on the existing system expansion plans developed by the utilities in each of the provinces based on established and commercialized technologies for system expansion.

However, when looking to the evolution of the energy landscape to 2050, there is significant potential for all provinces to reduce the carbon intensity of the electricity system and to expand the share of electricity in final energy consumption.

A balanced portfolio of renewables (wind and solar with storage) integrated with baseload generation options (nuclear, hydro, geothermal) and natural gas for peaking purposes is necessary for a reliable, flexible and resilient overall system. The intermittency of variable renewable generation is compensated with large-scale energy storage systems for grid stability. Regional siting of major hydro, nuclear and geothermal technologies from British Columbia to the Prairies to Ontario, Quebec and Atlantic Canada introduces diversity and flexibility to enhance trade from east to west.

Table 3: Canada’s Current System Expansion Plans (2025–2040) and Recommendations for Development (2040–2050) Per Province

| Province / Territory | Current System Expansion (to 2025–2040) | 2040–2050 Future Options |

| Ontario | 50 GW: 6,000 MW (Darlington small modular reactors (SMRs) 1,200; Bruce up to 4,800; hydro refurbishments; 3,000 MW storage) | Generation IV nuclear, broader SMR fleet, storage scale-up, renewables integration: wind/solar, hydro |

| Québec | 50 GW: 8,500 MW by 2035 (60 TWh Hydro-Québec plan, hydro/wind expansion, 600 MW seasonal exchange with Ontario) | Expanded hydro, wind, storage, hydrogen exports, interprovincial trade |

| Alberta | 30 GW: 1,365 MW renewables (Buffalo Plains, Travers, Paintearth, Dunmore), coal phase-out, gas as backup | Enhanced geothermal (using oil and gas expertise), advanced nuclear (SMRs, integral fast reactor [IFR]), long-duration storage, hydro imports (Mackenzie River project), wind/solar |

| British Columbia | 15 GW: 4,062 MW (Site C 1,100; Calls for Power ~2,962), $36B transmission upgrades | Expanded hydro, large-scale storage (pumped hydro), wind/solar, geothermal potential |

| Manitoba | 8 GW: 652 MW (600 MW wind call; Pointe du Bois 52 MW upgrade) | Expanded hydro, wind/solar with storage |

| New Brunswick | 5 GW: 2,200 MW (1,400 wind; 200 solar; 600 SMR) | Next-generation SMRs, offshore wind, hydrogen integration, tidal |

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 4,050 MW (Bay d’Espoir U8; Churchill Falls uprate; Gull Island ~3,900 potential; offshore wind-to-hydrogen export) | Offshore wind-to-hydrogen, expanded Churchill/Gull Island hydro, storage integration, tidal |

| Nova Scotia | 4 GW: 550 MW (local renewables + solar); offshore wind roadmap (5 GW by 2030); hydrogen hubs (EverWind, Bear Head) | Offshore wind and hydrogen hubs, tidal energy potential, storage |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 GW: 30 MW (Eastern Kings windfarm expansion); imports from NB; net-zero grid target by 2040 | Offshore wind, interties for reliability, tidal power |

| Saskatchewan | 3,375 MW (wind/solar up to 3,000; first SMR 315 by 2034; ~60 MW hydro uprates) | Full-scope nuclear (uranium fuel cycle, SMRs, IFR), geothermal, storage, gas, hydro |

| Yukon | Existing hydro, diesel, wind; microgrid pilots (Haeckel Hill Indigenous wind 2024) | Expanded hydro, solar-wind hybrid with storage, microgrids |

| Northwest Territories | 60 MW (Taltson hydro expansion; diesel backup) | Mackenzie River hydro complex (~13,000 MW potential), Intertie to Alberta/SK |

| Nunavut | 1.8 MW (diesel-dominated; small hybrid projects in Naujaat, Rankin Inlet) | Hybrid solar-wind-storage systems, community microgrids, long-term small nuclear options |

Source: Extracted from provincial system expansion plans (see Appendix A).

Generation: Emerging Options and Concepts

Drawing upon the insights emerging from the global summit report Equinox Blueprint Energy 2030: Energy 2030 – A Technological Roadmap for a Low-Carbon, Electrified Future (WGSI 2012), the choices, options and pathways for clean electricity generation solutions that constitute the building blocks of a national system are described and highlighted. For meeting the high growth in demand for electricity in the coming decades, a suite of innovative technologies and emerging concepts, it is necessary to consider options beyond projects in the existing system expansion plans. Highlighted below are emerging options and concepts that include hydro, wind and solar with large-scale storage, geothermal and nuclear.

Hydro

Canada has a long history of the development of major hydro projects, and hydro power remains an important source of clean energy that contributes to the low carbon intensity of Canadian electricity generation. The existing system expansion plans across Canada (mainly BC, Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and Atlantic Canada) include several new hydro projects with increased capacity.

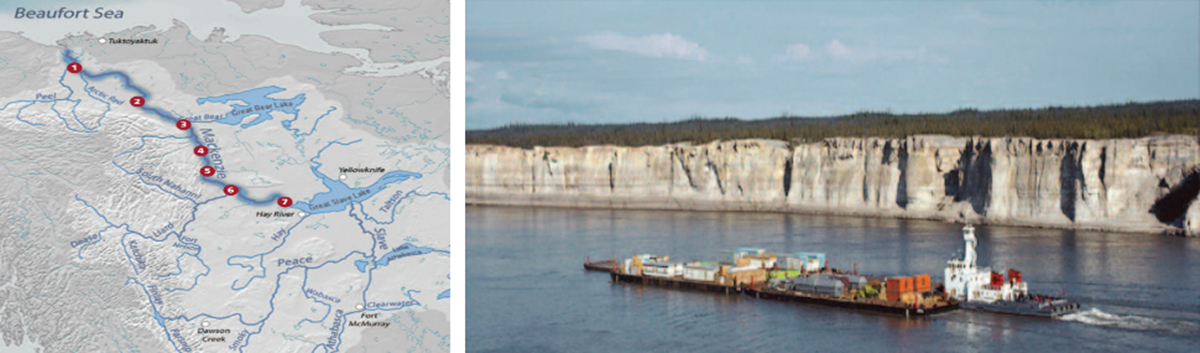

The Mackenzie River Complex: In addition to the planned increases of hydro capacity, a recent (2015) study of the potential of harnessing the Northwest Territories’ Mackenzie River for hydro power on a massive scale is a contender for further evaluation (Gingras 2015). Such a development could be advanced in the 2035–2050 time frame with detailed technical, economic and site evaluations and decision timelines in the 2025–2035 time frame. Such a project is consistent with the vision outlined here, predicated upon a massive increase in clean electricity production to displace fossil fuels from the economy. By any standard, the proposed project is enormous, similar in scale to Quebec’s giant James Bay Hydroelectric Complex.

The Mackenzie River’s significant hydroelectric potential, if developed, yields an overall capacity of ~13,000 MW, with a capacity factor of 80 percent availability. Characterized by flows of up to 9,000 cubic meters per second per second, steep shorelines avoiding wide-area submersion and large lakes acting as flow regulation reservoirs, the Mackenzie River project includes an upstream water control structure, six downstream powerhouses and 10,000 km of transmission lines to bring the power to Edmonton.

The complex would generate 92 million MWh annually, equivalent to producing 525,000 barrels of oil per day. This clean energy could be part of a cleaner mix of supply for Alberta (10,000 MW) and Saskatchewan (3,000 MW) to allow a transition from use of high-carbon footprint thermal generating stations to low-carbon hydroelectric power stations. For investment decisions, the project development can be staged and timelines sequenced to match requirements as thermal generating stations approach the end of their expected life spans.

The Mackenzie River presents several unique characteristics. First and foremost is the fact that its riverbanks are generally steep, from 15 to 40 m, that dams of 20 to 30 m would flood only a very limited area, despite the river’s enormous power generating potential. The proposed development consists of seven individual projects, including one water control structure and six run-of-the-river electric power generating stations, harnessing a combined head of 138 m, and representing a capacity of over 13,000 MW (Figure 27). Additional projects may also be envisaged on the Great Bear, Liard and Slave Rivers.

To connect the Mackenzie Hydroelectric Complex to the Alberta power grid near Edmonton, some 10,000 km of transmission lines will be needed, based on a 735 kV transmission technology scenario, a technology pioneered in Canada and used successfully in both Quebec and the United States for nearly 50 years. At an estimated present cost of 1.5 million dollars per km (2015 data), a single line has a transmission capacity of approximately 2,000 MVA; 10,000 km of 735 kV lines would therefore cost approximately $15 billion. Incorporating appropriate static VAR compensation, line capacity can be increased to approximately 2,800 MVA.

Figure 27: Mackenzie River Hydroelectric Complex

Site of the Mackenzie – 2 Project (Bassin des Murailles) and Map of the proposed Mackenzie River hydroelectric complex. Note the steep riverbank typical of the Mackenzie River landscape. Source: Gingras (2015).

The project cost estimates and an assessment of financial viability would need to be updated and more detailed analysis of all technical aspects would be necessary. This major hydro power development on the Mackenzie River is highlighted as a potential contributor to the national mix of clean energy generation in the 2040–2050 time frame. It is a major undertaking and has not yet been identified as part of the system expansion plans by any of the provinces.

Large-scale Solar and Wind with Storage

Solar and wind offer substantial potential for electricity production with no direct contribution to GHG emissions. Even from a total lifecycle GHG emissions footprint standpoint, solar and wind energy emissions are a small fraction of what coal, oil, or natural gas would emit. To meet the 80 percent electrification end-state vision, a substantial increase in the installed capacity of wind and solar will be a necessary contribution to a low-carbon energy system. As shown in Table 2, deployment of ~1500GW solar and ~700GW of wind capacity is envisaged given lower capacity factors of the resources.

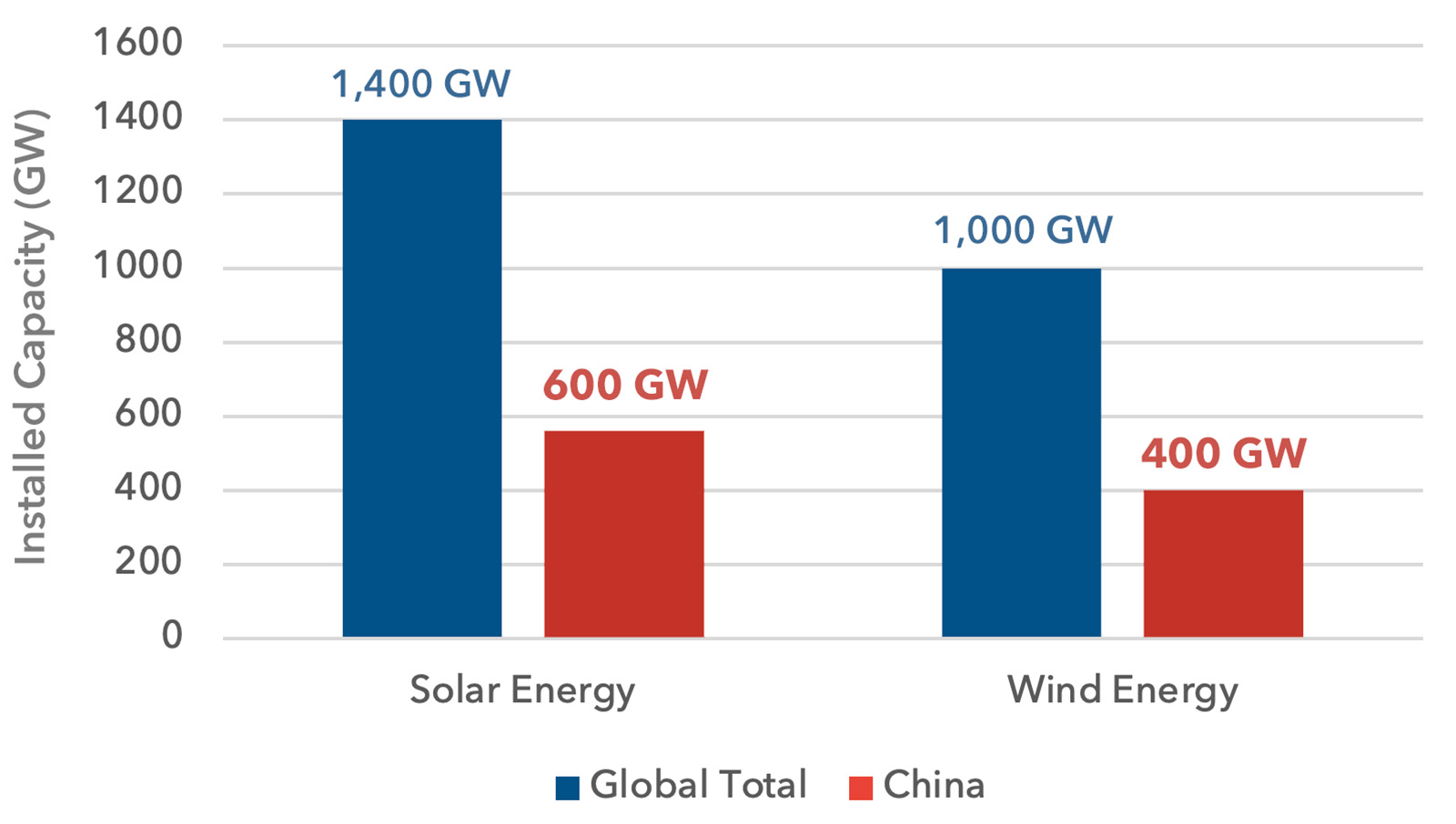

Globally, the scale of solar and wind energy installations has grown dramatically with an installed solar capacity of about 2200 GW and about 1136 GW of wind capacity at the end of 2024. The leading countries to date are China (by far the largest) with the United States, India and Germany among the top four. As a block, the European Union also has a large amount of solar and wind installed capacity – approximately 338 GW and 231 GW of solar and wind installed respectively at the end of 2024. In particular, the International Energy Agency (IEA) has indicated that solar energy has become the cheapest source of new electricity, which explains why solar power (specifically utility-scale and distributed PV) is the largest source of new electricity-capacity additions globally in recent years. Per The IEA’s “Renewables 2025” report, global annual solar PV additions for 2025 will be nearing ~600 GW which is truly astounding.

Figure 28 provides a current snapshot of the dominant share of wind and solar installed capacity in China compared to the global installed capacity. China leads in manufacturing, deployment and innovations in solar and wind technologies with greater than 40 percent of the global share. The shift towards renewables is accelerating due to cost competitiveness, climate commitments and technological advances including China’s great focus and strides to electrify its energy landscape and prepare for ever increasing energy demand.

Figure 28: A Graph Demonstrating Global vs. China’s Installed Capacity of Solar and Wind Energy

Source: Authors, data compiled from IEA (2025).

The variable and intermittent nature of solar and wind electricity generation means that they are only partially dispatchable, thus requiring large-scale storage for effective integration into electricity supply grids. The quality of solar and wind resources also varies across provinces. In this regard, the role of natural gas will remain critical as a peaking resource for the grid. A national grid as the backbone of an electrification strategy which also incorporates large-scale storage capacity is another key feature enabling a trading system for large transfers across provincial jurisdictions over long distances as part of an overall optimized national electricity grid.

Large scale storage is, therefore, an important requirement and a technology option to enable solar and wind to “mimic” the characteristics of baseload generation and subsequently assume a greater role within the national energy supply mix. Effective use of grid-scale storage will also minimize the need to curtail solar and wind generation when there is grid congestion, transmission limits, and/or any overall system imbalances.

As renewables penetration continues to expand in many countries and regions, the intermittency issue will require a combination of innovative grid management techniques, smart grid technologies, dispatchable back-up resources, and increasing use of energy storage. Several options exist and have been implemented around the world for managing the variability of wind and solar resources, each with strengths and weaknesses that differ across scale and situation. These include the use of natural gas generation as a complement to wind output generation, demand management or storage.

As stated earlier, solar and wind coupled with large-scale storage can provide energy on a large scale with characteristics that nearly match those of baseload power. Increased storage capability with effective integration of smart grid technologies at the distribution level offers the most promising pathway for reducing overall costs and decreasing transmission system load and imbalances.

There has been a dramatic rise in the deployment of energy storage in different parts of the world primarily thanks to the exponential growth of renewables, in particular solar energy. Energy storage products have now been successfully deployed in high numbers across residential, commercial, and utility sectors in various countries. As expected, most deployments (in terms of total capacity) have been due to utility-scale installations. Top five countries in the world for energy storage are China, US, UK, Australia, and Chile with approximately 314 GWh of capacity at the end of 2024. China by far leads total installations with 64 percent of 315GWh followed by the US at 26 percent (Visual Capitalist 2024; Elements 2024; IEA 2024).

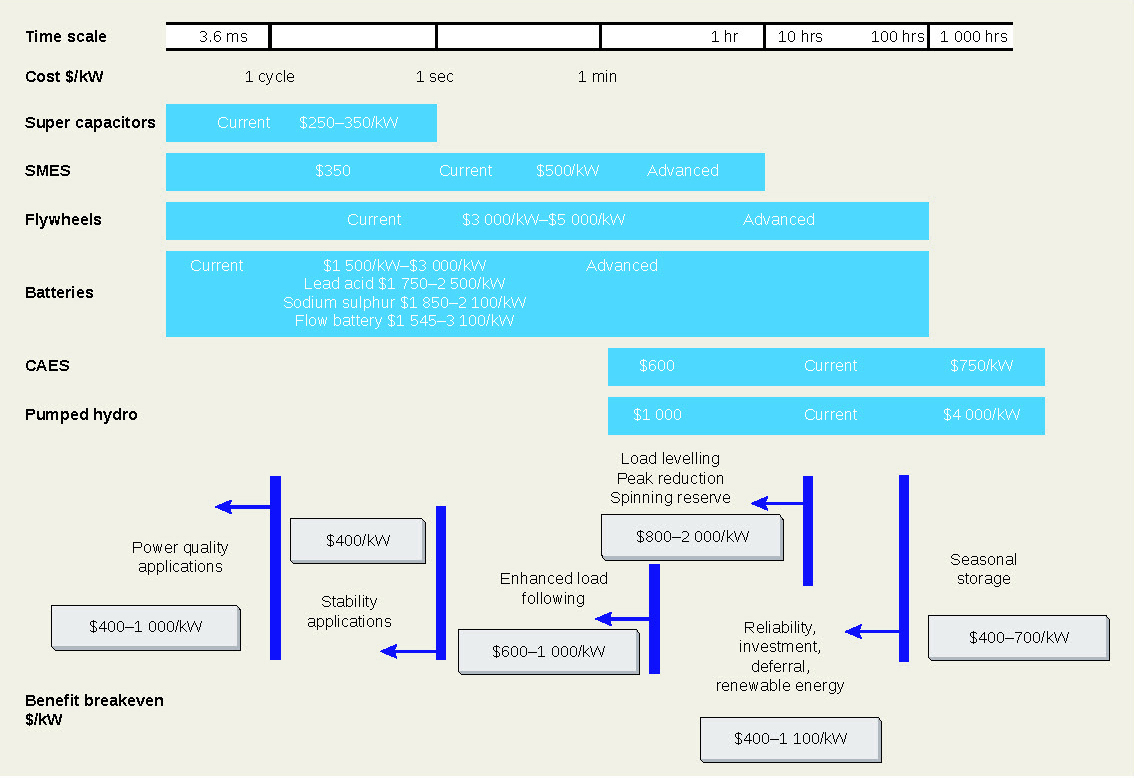

The evolution of energy storage both in terms of cost and technology has been very interesting providing great insights into effective technology selection and development and how costs can indeed be dramatically reduced with efficiency and volume. For instance, at a major clean energy and energy electrification conference held at the University of Waterloo, in Canada in February 2012 (WGSI), although in many ways at its infancy at the time, the potential for grid-scale energy storage and its benefits were highlighted and discussed as shown in Figures 29 and 30 below. Although some of the technologies highlighted then such as supercapacitors and flow batteries remain key areas of interest with unique attributes, the main energy storage technology of today evolved to be based on Lithium-Ion chemistry dominating all new energy storage installations meeting many of the grid services requirements. There is no doubt there will be further innovation in energy storage and other chemistries resulting in on-going cost and performance improvements. The key point to be made, however, is that energy storage costs of the current offerings have dropped so dramatically that large-scale deployments to meet a variety of system needs including addressing intermittency of large solar and wind installations is completely practical.

Figure 29: A Historical Perspective on Potential Grid-Scale Storage Solutions

Source: WGSI (2012), compiled from data from Culver (2010).

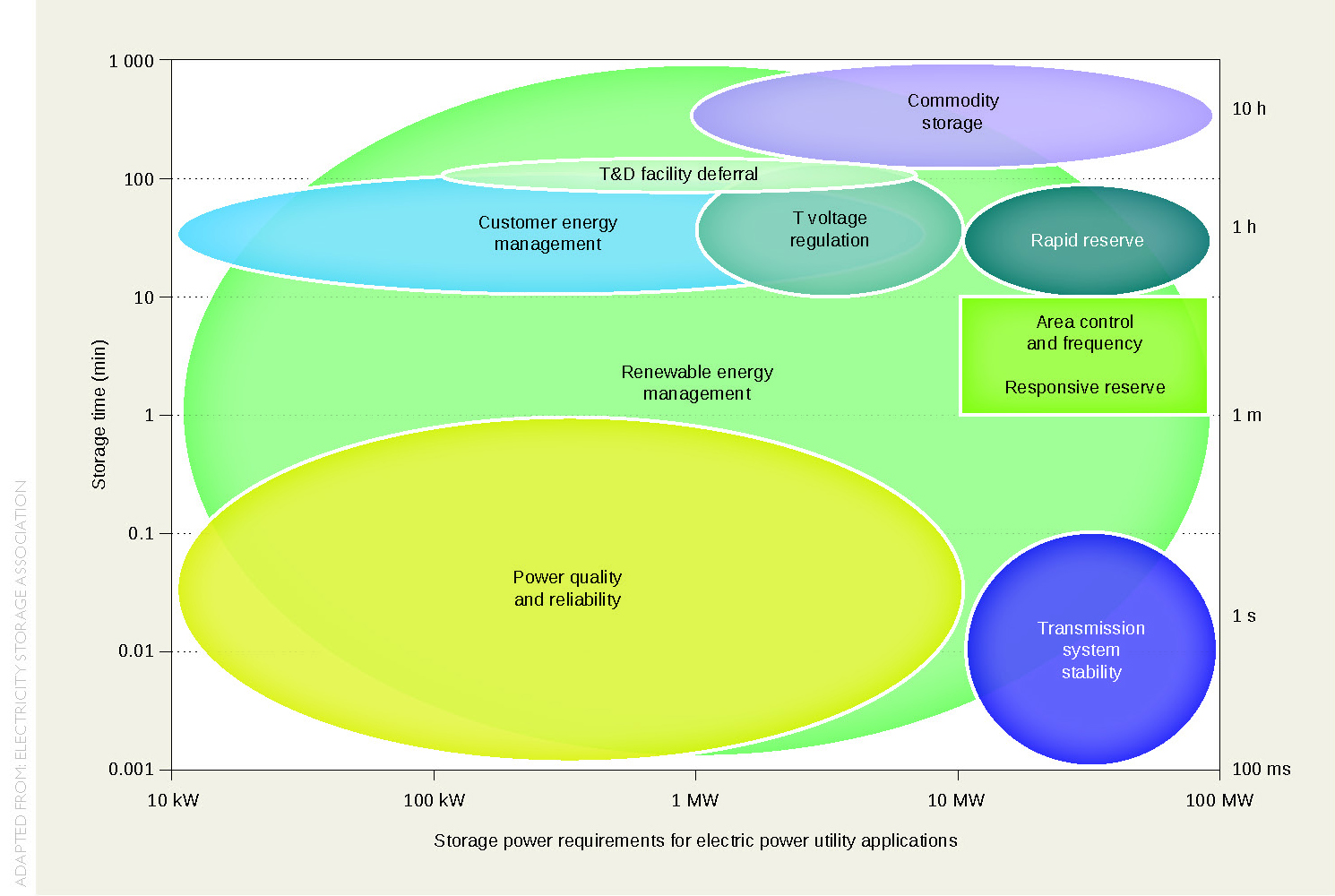

As shown in Figure 30, no single storage system can match the multiple device requirements for large-scale grid application; the capabilities must be matched to the context and specific requirements of the grid operator.

Superconducting magnetic energy storage (known as SMES) can deliver energy across a wide range of timescales, providing rapid response and exceptionally high efficiency, which makes them particularly well-suited for stabilizing grids with high shares of intermittent renewable energy. With storage capacities of up to 5,000 MWh, they represent a powerful option for large-scale renewable integration alongside battery technologies (Ali, Woo and Dougal 2010).

Figure 30: Storage Power Requirements for Power Utility Application

Source: WGSI (2012, 60).

In summary, solar and wind capacity, installed on a large scale and coupled to storage, will allow provinces to maximize their contributions to the national grid based on their own unique solar and wind potential. Furthermore, large growth in the deployment of these technologies will create new engineering, manufacturing, and service sectors in Canada by localizing the production and support of the corresponding components and systems for solar, wind, and storage.

Strategic placement of solar and wind capacity, integrated into a national grid, allows for significant optimization of cost through daily or seasonal arbitrage of energy supply and demand. The reduced prices for consumers can only be realized as a national benefit through a grid that serves all provinces.

Geothermal Power

Geothermal energy is a large resource capable of providing a significant proportion of energy demand. The immediate potential for geothermal resources to play a major role in Canada’s clean energy transition is geothermal energy for buildings. Air source and ground source heat pumps (Geoexchange) are commercially established technologies for use in buildings, providing a cost-effective pathway to displace natural gas for heating and cooling requirements.

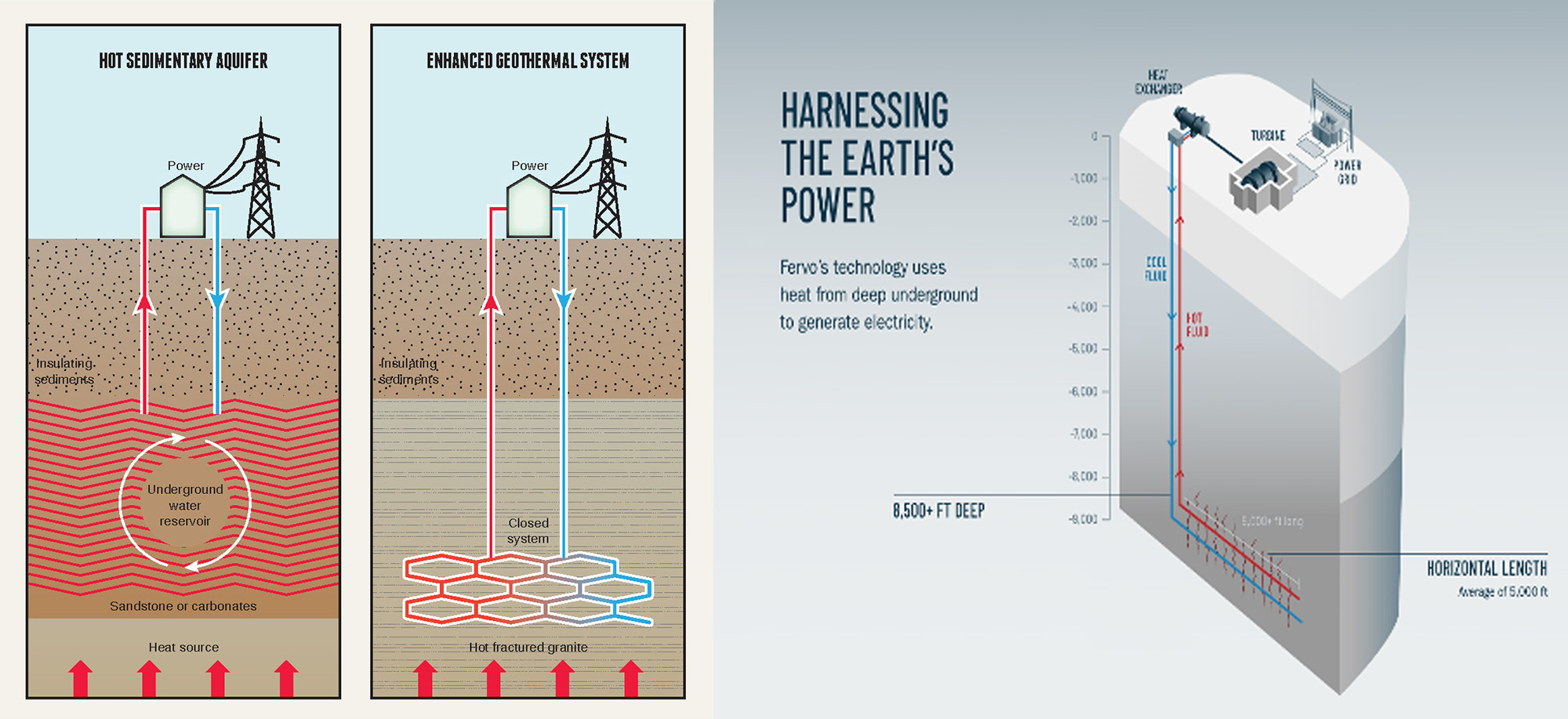

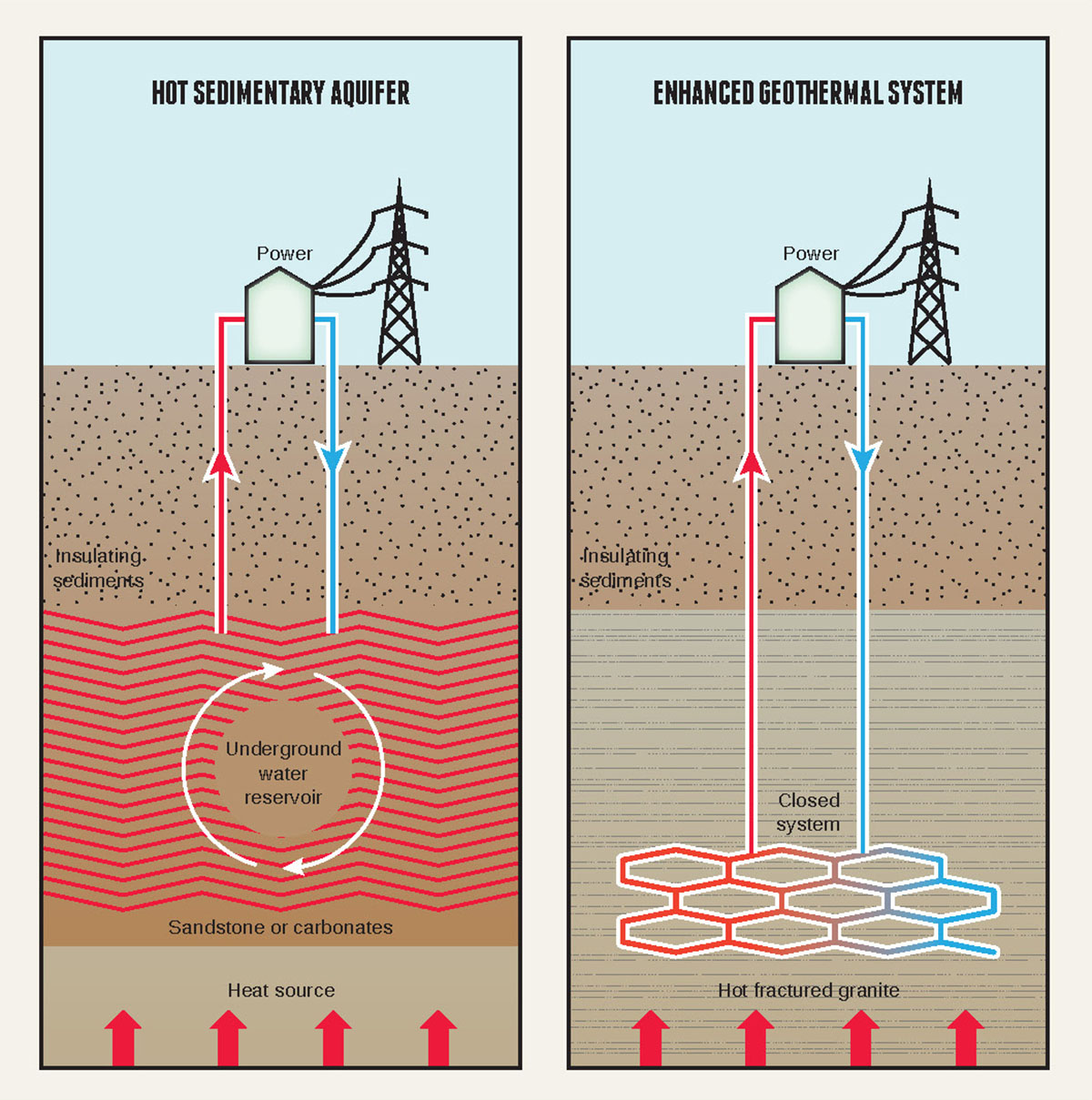

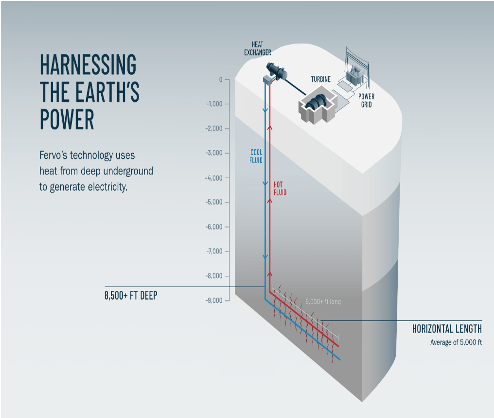

Deep geothermal resources at depths greater than 1 km to 10 km (enhanced geothermal systems [EGS]) offer limitless potential for electricity generation without geographic limitations.7 Research and technological challenges — primarily related to drilling costs — are being addressed. Demonstration of scale applications as well as demonstration projects to “de-risk” the technology show promise and allows a pathway for investors to finance specific projects (Norbeck and Latimer 2023).

Shallow Geothermal Resources for Building Heating and Cooling

Ground source heat pumps (GSHPs) combined with air source heat pumps (ASHPs) offer the option to displace natural gas directly and can play an important role in reducing grid-related system costs in a renewable-heavy grid. Building heating is a major driver of peak winter electricity demand in Canada, and widespread electrification without sustainable technology choices could impose significant consumer costs.

Widespread deployment of shallow geothermal energy resources for commercial, industrial and residential direct heating purposes is the most direct and cost-effective pathway for efficient home heating and cooling. Net-zero homes with good building design and geothermal as the primary resource for heating coupled with solar and storage batteries in a VPP configuration is a practical and feasible choice.

A recent study from the Canadian Gas Association (2019), “Implications of Policy-Driven Electrification in Canada,” highlights several scenarios and challenges, indicating high costs of a scalable national level electrification.

By contrast, when GSHPs are incorporated into the modelling, the projected costs decline sharply. With a 10–30 percent market share, GSHP adoption could reduce total costs by $49–$148 billion over 30 years, while full adoption would yield nearly $500 billion in savings. The savings stem from GSHPs’ superior efficiency in cold climates. Unlike ASHPs, they do not experience significant performance degradation in winter, thereby reducing peak electricity loads and lowering associated generation and transmission costs. Although GSHPs are more expensive to install, the decrease in system-wide electricity generation ($494 billion) and energy costs ($137 billion) far outweighs the additional $137 billion in equipment expenses under full adoption.

A comprehensive analysis of grid costs and the benefits of a national-scale mass deployment of geothermal heat pumps across the United States (2022–2050), based on commercially available technology, yields an undiscounted cumulative savings of more than US$1 trillion for the grid decarbonization scenario (Xiaobing Liu et al. 2023) to 2050.

Ground source heat pumps installed with energy efficient building envelopes in single family homes can become primarily a grid cost reduction tool when deployed on a national scale. Even in the absence of any other decarbonization policy, GSHPs offer the benefits of a substantial reduction of CO2 emissions, GSHPs reduce the cost of power on the grid, as well as the marginal system cost. Policy makers could create targeted incentives that encourage GSHP adoption and avoid strategies that inadvertently exclude this cost-saving technology from Canada’s decarbonization goals. Large-scale deployment of GSHPs lowers grid infrastructure investment, as well as reduces the cost of power for all grid consumers — even those who do not have the technology installed.

Enhanced Geothermal Systems for Electricity

With deep drilling (more than 4 km), enhanced geothermal power systems can provide an abundant source of clean baseload electricity from hot dry rock sites without geographic limitations. Enhanced geothermal power is a renewable energy resource available anywhere in Canada with the greatest potential for development in Alberta and Saskatchewan. Given the strength of geotechnical expertise (drilling and extraction capabilities of the oil and gas sector), investing in EGS alone could provide a large share of electricity demand. If the oil and gas sector can pivot away from fossil fuels extraction to geothermal, it makes this resource a complementary technical option to the use of variable resources such as wind and solar, helping to stabilize grids as they expand and make an important contribution to reduction of carbon emissions.

Source: Gates (2025).

Demonstration phase EGS projects are underway in several countries: France, Germany, Finland, Australia, while the United States has revived a national geothermal program for EGS (Alijubran and Horne 2024; U.S. Department of Energy 2019; Augustine 2016).

The first phase of an operating plant in Nevada, with a 400 MW capacity when completed in 2028, has been commissioned by Fervo Energy at Cape Station.8

Overall, geothermal resources for electricity generation (Schulz and Livescu 2023; Geothermal Resources Council 2016; Roberts 2018) and shallow geothermal resources (GSHPs and ASHPs) offer the most promising pathway for displacing fossil fuels: heating and cooling services in buildings and electricity for transport and industry.

Source: WGSI (2012, 66). . Source: Gates (2025).

Demonstration phase EGS projects are underway in several countries: France, Germany, Finland, Australia, while the United States has revived a national geothermal program for EGS (Alijubran and Horne 2024; U.S. Department of Energy 2019; Augustine 2016).

The first phase of an operating plant in Nevada, with a 400 MW capacity when completed in 2028, has been commissioned by Fervo Energy at Cape Station.8

Overall, geothermal resources for electricity generation (Schulz and Livescu 2023; Geothermal Resources Council 2016; Roberts 2018) and shallow geothermal resources (GSHPs and ASHPs) offer the most promising pathway for displacing fossil fuels: heating and cooling services in buildings and electricity for transport and industry.

Source: WGSI (2012, 66). Source: Gates (2025).

Demonstration phase EGS projects are underway in several countries: France, Germany, Finland, Australia, while the United States has revived a national geothermal program for EGS (Alijubran and Horne 2024; U.S. Department of Energy 2019; Augustine 2016).

The first phase of an operating plant in Nevada, with a 400 MW capacity when completed in 2028, has been commissioned by Fervo Energy at Cape Station.8

Overall, geothermal resources for electricity generation (Schulz and Livescu 2023; Geothermal Resources Council 2016; Roberts 2018) and shallow geothermal resources (GSHPs and ASHPs) offer the most promising pathway for displacing fossil fuels: heating and cooling services in buildings and electricity for transport and industry.

Nuclear Power

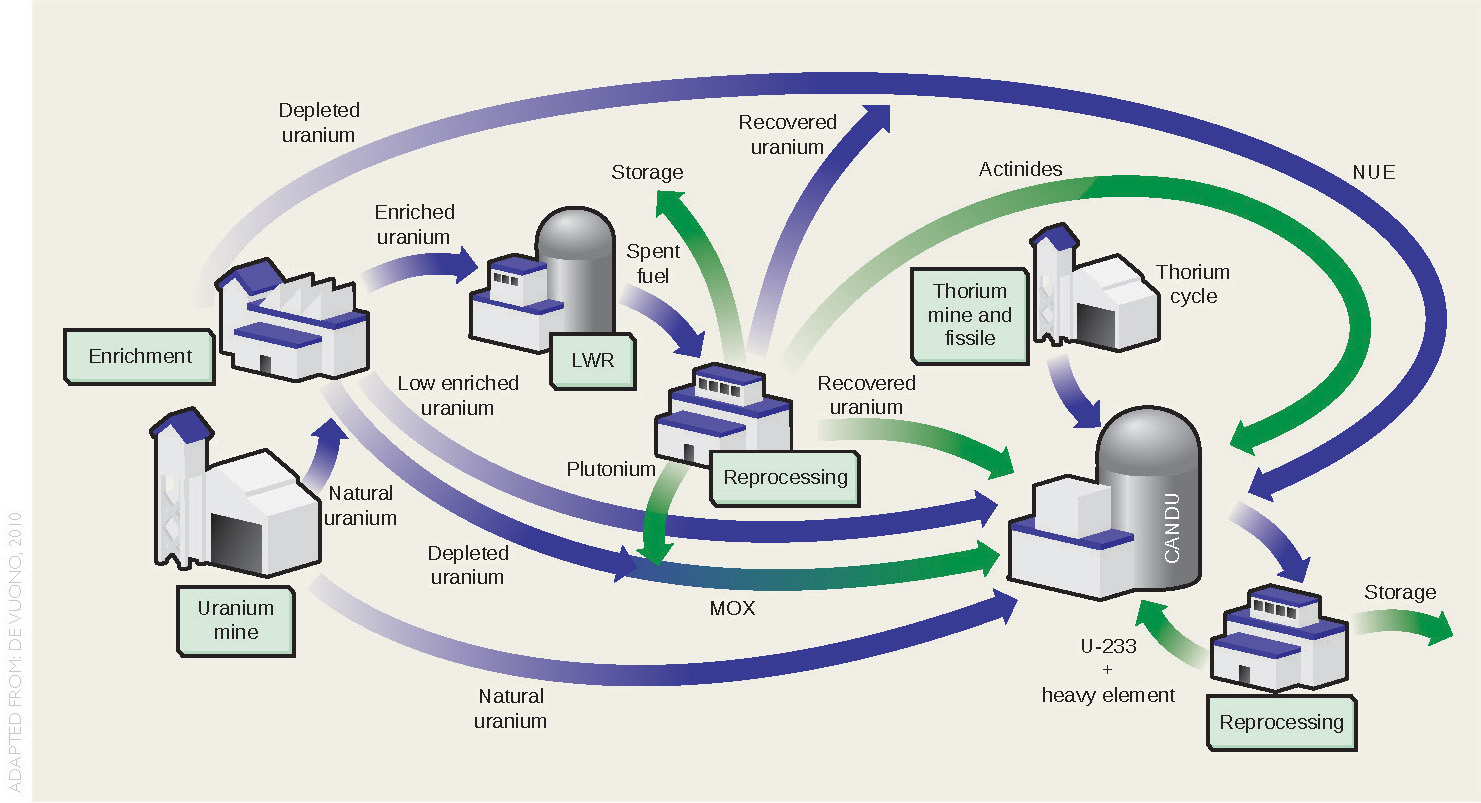

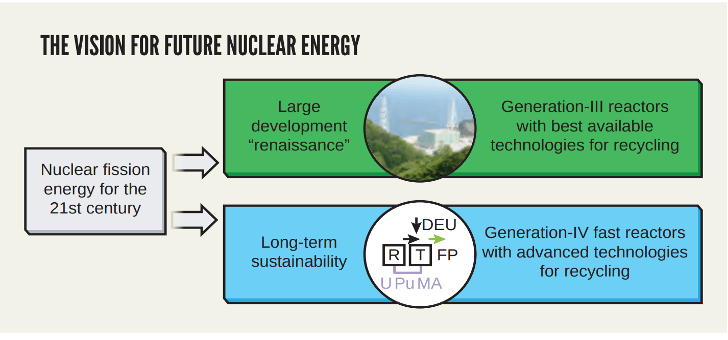

A significant build-out of the existing technological base9 (namely, Generation III+ reactor systems) — and a widespread adoption of Generation IV technologies that comprise fast neutron reactors with closed fuel cycles to reduce nuclear waste — offers the possibility of providing energy on a terawatt scale, making nuclear fission sustainable over many decades to come.

Among the low-carbon options that are currently available for energy generation, nuclear power is unique in that it harnesses an energy source that is more highly concentrated than fossil fuels. This occurs despite the fact that reactors currently deployed almost exclusively use thermal neutrons, which extract less than one percent of the fuel’s energy content. If Canada is to move away from reliance on GHG-producing fossil fuels in electricity generation, it is difficult to imagine how this can be achieved without a transition to advanced nuclear technologies.

Advanced nuclear technologies hold enormous potential to become a significant part of the future baseload picture. These novel design concepts aim to close the nuclear fuel cycle by eliminating high-level nuclear waste, reducing the threat of proliferation and providing an inexhaustible source of energy.

Figure 33: Advanced Nuclear Fuel Cycle Concepts Allow for better Utilization of Uranium and Close the Nuclear Fuel Cycle

Source: WGSI (2012, 74).

While these Generation IV design concepts are an excellent example of the scalability and potential of nuclear energy, they need to be understood within the array of nuclear technologies available. From the perspective of a long-term energy transition, an expansion of the existing base of established Generation III reactor technologies in the near-term provides a credible pathway for a phased transition to Generation IV technologies.

As Canada seeks to reduce dependence on fossil fuels and accelerate the transition to a low-carbon electricity system by 2050, advanced nuclear technologies can complement existing renewable resources. New reactor designs, such as the Integral Fast Reactor (Archaambeau et al. 2011; Hannum et al. 2005) designs and the emerging SMRs can provide reliable, low-carbon baseload electricity to support electrification of transport, heating and industry.10 These reactors help close the nuclear fuel cycle by reusing and burning nuclear waste, reducing long-term storage requirements and operating with liquid metal coolants at near-ambient pressures, which minimizes the risk of loss-of-coolant accidents. Importantly, these designs are incompatible with weapons proliferation, helping address longstanding public concerns related to nuclear technologies (International Atomic Energy Agency 2020; Ultra Safe Nuclear Corporation 2024; General Atomics Electromagnetic Systems 2025; World Nuclear Association 2025).

Figure 34: Future for Nuclear Energy

Source: WGSI (2012, 79).

Accelerating the development of these technologies would require updates to regulatory frameworks and broader public acceptance. With an existing base of nuclear expertise in the design and operation of large nuclear reactors in Ontario and an established supply chain to support nuclear expansion in Canada, the next step in developing national prowess is to further develop Saskatchewan’s uranium resource for added-value creation along the chain.

The re-imagined future for the nuclear sector is for Canada to become a provider of full-scope nuclear fuel cycle services — mining, fabrication of fuel for different customer markets, reprocessing of existing high-level used fuel and advancing next generation reactors capable of re-using the waste for electricity generation. This could be led by Saskatchewan and Ontario. For the 2035–2050 time frame, this is a compelling pathway for abundant energy supplies to fuel the transition to electricity.

Endnotes

7. Recent Cascade Institute Reports provide key insights for advancing deep geothermal in Canada: Graham et al. (2022); Pearce and Pink (2024); Smejkal, Cosalan and Cortinovis (2025). Also see www.ga.gov.au/aecr2024/geothermal.

8. The plant came online in 2023 with a capacity of 3.5 MW — enough to provide power to about 2,600 homes. With drilling of 24 planned geothermal wells at the facility, the plant is expected to start generating 100 MW of power in 2026 and an additional 400 MW will come online in 2028. See https://fervoenergy.com/.

9. See Brouillete (2022, 7) and Canadian Nuclear Association (2024).

10. Several recent developments in Canada include: “Feasibility of Small Modular Reactor Development and Deployment in Canada” by SaskPower, Énergie NB Power and Ontario Power Generation (2021), Canadian Small Modular Reactor Roadmap Steering Committee (2018); InterProvincial Government (2022).