Despite growing international and domestic governance approaches for Responsible Investing (RI) incorporation, in the summer of 2021, five of Canada’s largest investment funds, increased their investments in Canada’s oil sands. This comes despite promises made by these portfolios to decrease their environmental impact and commit to RI, which, importantly, they note may come from exercising their voting rights to act as advocates for responsible business practices in the companies they are invested in, rather than simply divesting their funds.

Responsible investing (RI) has become a hot topic in the global investment world and has gained momentum over the last decade.1 Attempts by global governance actors, such as the United Nations, to develop standardized policies for RI integration have been taken up by national governments. In Canada, for example, crown corporations are required to adopt the recommendations and disclosures of the Task Force for Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) by 2022.2 Despite growing international and domestic governance approaches for RI incorporation, in the summer of 2021, five of Canada’s largest investment funds, including the management funds for provincial pension plans in both Quebec (QC) and British Columbia (BC) as well as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, increased their investments in Canada’s oil sands.3 This comes despite promises made by these portfolios to decrease their environmental impact and commit to RI, which, importantly, they note may come from exercising their voting rights to act as advocates for responsible business practices in the companies they are invested in, rather than simply divesting their funds.4

This paper will evaluate a number of public service pension plans from across Canada to understand how RI is incorporated into their investment policies. Statements of Investment Policy and Procedures (SIPPs) and Responsible Investing Policies (RIPs) for public service pension plans across the country will be analyzed. The three central questions are: How do public pension funds incorporate international and national best practices of responsible investing set by global governance actors into their investment policies? How are recent actions in line with their current investment policies? Why do variations in alignment with global governance bodies occur between public service pension plans?

Findings from this preliminary sample show it is portfolio size, rather than geography, that increases specificity and action with regard to RI practices. These findings will be of interest to practitioners in the investment field seeking to incorporate RI into their practice. This preliminary data aims to contribute to the ongoing discussion on RI across public sectors by providing insight into RI integration across the selected plans.

RI Context

RI is an approach to investing that incorporates environmental, social and governance (ESG) criteria into the investment decision-making process.5 Although RI began as a response to stocks of companies that profited from vices such as gambling, tobacco and alcohol,6 more modern RI sees investments made based on investor values, not necessarily withdrawn in response to specific negative actions.7 Much of the debate around current RI, however, focuses on both its necessity and its ability to produce returns for the investor. Supporters of RI have noted that RI such as selecting investments based on their ESG performance, has the potential to increase returns compared to choosing investments without such considerations.8 Opponents of RI suggest that utilizing RI screening inherently lowers portfolio diversity, creating unnecessary risk for investors.9 Regardless of its impacts, investment professionals have often noted that they are unequipped to incorporate RI properly.10

RI in Pension Plans

Much like the debate on RI in general, RI integration in pension plans is a contested concept. Past research has pointed to the inherent tension of public pension plans serving the best interests of governments and thus having a responsibility to all citizens, but at the same time having a specific duty to achieve returns for pensioners.11 Especially given their need for long-term sustainability12 and the ability of RI to increase public perception,13 pension funds have specifically been seen as fertile grounds for RI integration. The incorporation of RI does not necessarily need to come in the form of divestment, but can also include activism within investments.14

The results of research into pension plan integration, however, is, as would be expected, mixed. Some research has shown that integrating RI can expand diversification and thus limit risks.15 Others have pointed to inconclusive results of fund performance with RI integration16 and fears of lower returns as well as a general lack of awareness and information on RI for investment managers and pensioners17 as a justification for not integrating RI. Ultimately, while the largest and smallest pension plans integrate RI the most,18 financial interests are still the dominant drivers of public pension plans investments.19

Global Governance of RI

In response to much of the above debate, there are numerous international policy documents that have attempted to layout concrete steps for RI integration. Of these policies, there have been two major global governance actors whose impact has permeated the Canadian investment frontier as particularly relevant for RI integration, namely: the Financial Stability Board’s Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) and its “Recommendations” published in 2017; and the United Nations Environment Programme Finance Initiative (UNEP FI) an outgrowth of the work of the United Nations Principles for Responsible Investing, and its “Fiduciary Duty in the 21st Century: Final Report” published in 2020. These policies are not only widely utilized across industries, but are included in the Canadian government’s official recommendations for RI integration.20 Adapting from the approach of Ramani et al.21 it is on these global governance recommendation policies that this paper’s analysis of effective RI integration by Canadian public service pension plans will be based.

The TCFD22 points to the need for specificity in RI integration within investment policies. As a starting point, organizations should assess how climate factors will impact their investment portfolios, which will affect their risk when investing. The TCFD also notes that investment policies should be aligned with internationally recognized RI approaches, as well as the investment policies of other organizations in the same region. They should also provide disclosure statements as part of their regular reports, consistent with the reporting of similar organizations.

The UNEP’s report on fiduciary duty23 found that a discussion of ESG integration in investment policies is no longer an option, but rather a requirement of fiduciary duty. Organizations that do not comply with this requirement leave themselves open to legal challenges. Even if ESG factors are not incorporated, both individual and institutional investors face the fiduciary duty to consider how ESG factors will impact investment decisions, including noting how ESG factors might impact the short-, medium- and long-term returns of their investments. Further, how these ESG criteria are evaluated and either incorporated or not, must be clearly disclosed in investment policy statements. ESG integration can include screening out of investments or active ownership.

What is obvious from these governance documents is the need for specificity with relation to RI integration in investment policies. There is a broad recognition that, at this point in time, different organizations will be at different stages of readiness for RI incorporation, based on their current investment timelines and geographic placement. What is necessary, however, is evidence in investment policies that these factors have been meaningfully considered and are spelled out in a way in which they can be acted upon.

Methods

Participants

Participants for this analysis include 10 public service pension investment portfolios from across Canada. An initial search was conducted for the policies that had been reported to have been increasing their investment in the oil sands, which included two provincial pension plans (QC and BC) as well as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan. Given the inclusion of provincial investment plans, and for the purpose of comparison across the nation, an additional search was conducted specifically for pension plan investment policies for provincial public service. Three provinces did not have publicly available investment documents: New Brunswick, Saskatchewan, and Newfoundland and Labrador. The BC Teachers’ Pension Plan and Canada Post Pension Plan were also included for comparison. While not a complete sample of the entire Canadian public sector, this sampling allowed for investigation of the characteristics of plans that reinvested in the oil sands. Limitations are noted in the conclusion.

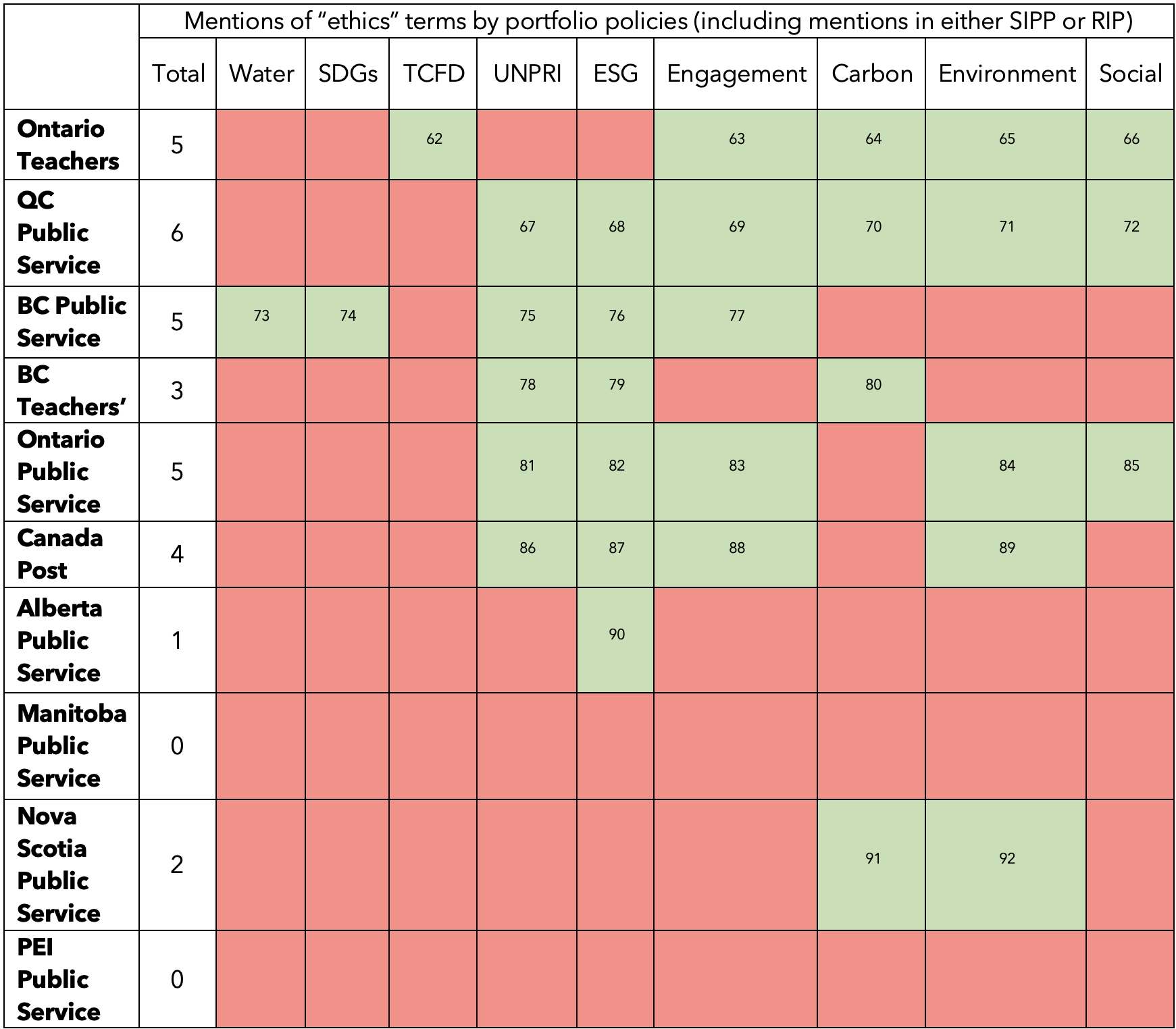

Participants and policies collected are noted in Table 1 below, with green indicating policies included and citations to the policies notes throughout. More detail on the process of data collection and justification can be found in the footnotes.24

Table 1: Investment Policies Collected with References

Data Analysis

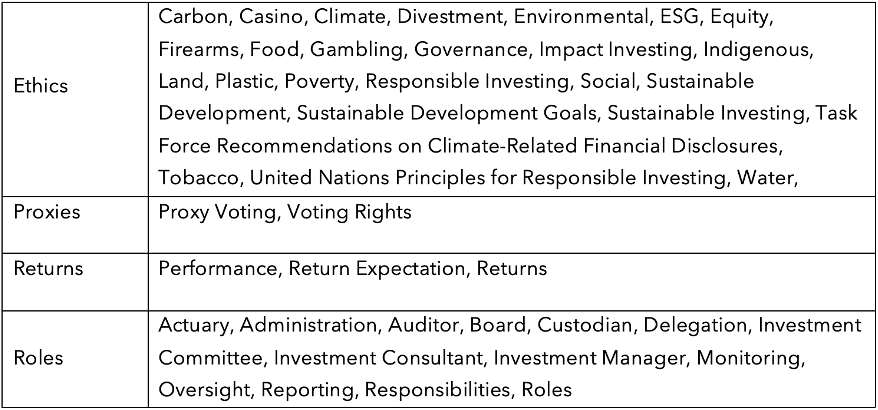

Documents were analyzed using the qualitative data analysis software NVivo. Codes were drawn from past research on RI in the higher education sector, which provides a strong basis for analysis of other pension SIPPs.51 Each term was coded in relation to their connection to RI either directly, or tangentially through reference to the practices related to RI. Codes included for analysis are noted below in Table 2.

Table 2: Codes Used to Analyze Investment Policies

Results

Results are presented here in three parts. The first analyzes the percentage of each SIPP committed to RI, with RIPs excluded as they are entirely RI focused. The second analyzes the use of ethics terms (identified in Table 2) in both SIPPs and RIPs. The third analyzes RI delegation and activism through voting in both SIPPs and RIPs.

Percentage of SIPPs Committed to RI

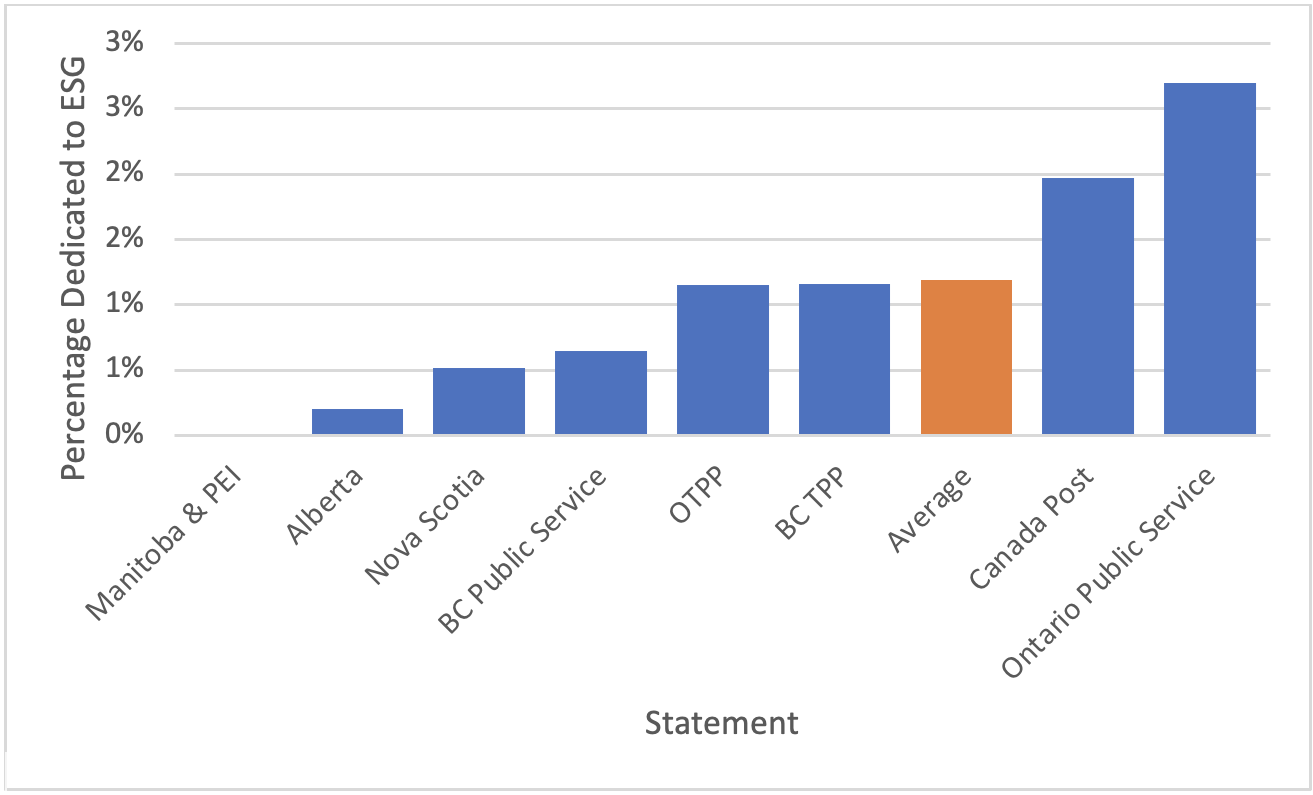

SIPPs that mentioned RI (often used interchangeably with ESG) were analyzed for the percentage of the document dedicated to RI to understand the depth in which RI considerations were included. RIPs were excluded from this analysis as the focus of these policies is exclusively on RI considerations. Of the nine SIPPs collected, seven52 specifically mentioned ESG/RI considerations (these terms are used interchangeable in SIPPs). Of the two SIPPs that did not include mention of ESG considerations, PEI53 does not mention ESG inclusion even vaguely, whereas Manitoba notes their policy does not include non-financial considerations.54 Results can be seen in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Percentage of SIPP Dedicated to RI

As shown in Figure 1, Alberta55 committed the least of its SIPP to RI with only .2 percent committed to RI. The Ontario Public Service Pension Plan56 committed the most with 2.7 percent of its SIPP discussing RI. The average SIPP committed 1.19 percent of its SIPP to RI considerations. For comparison, the average length of ESG integration is comparable to the average description of the role of the board (1.13 percent). Nova Scotia’s SIPP noted that it included ESG only insofar as it did not conflict with other investment objectives.57 Alberta’s SIPP further adds that its fiduciary duty for high returns overrides ESG considerations and therefore ESG considerations are not to take precedence over other investment objectives.58 By contrast, three portfolios59 specifically mention RI as a method by which to diversify the portfolio and therefore increase potential returns and decrease potential risks. Particularly interesting is that, while the six SIPPs with the longest RI-related segments all had separate RIPs, none of these policies referred to their RIPs within the SIPPs, which is the governing document for all investment practices.

RI Ethics Terms Included in SIPPs and RIPs

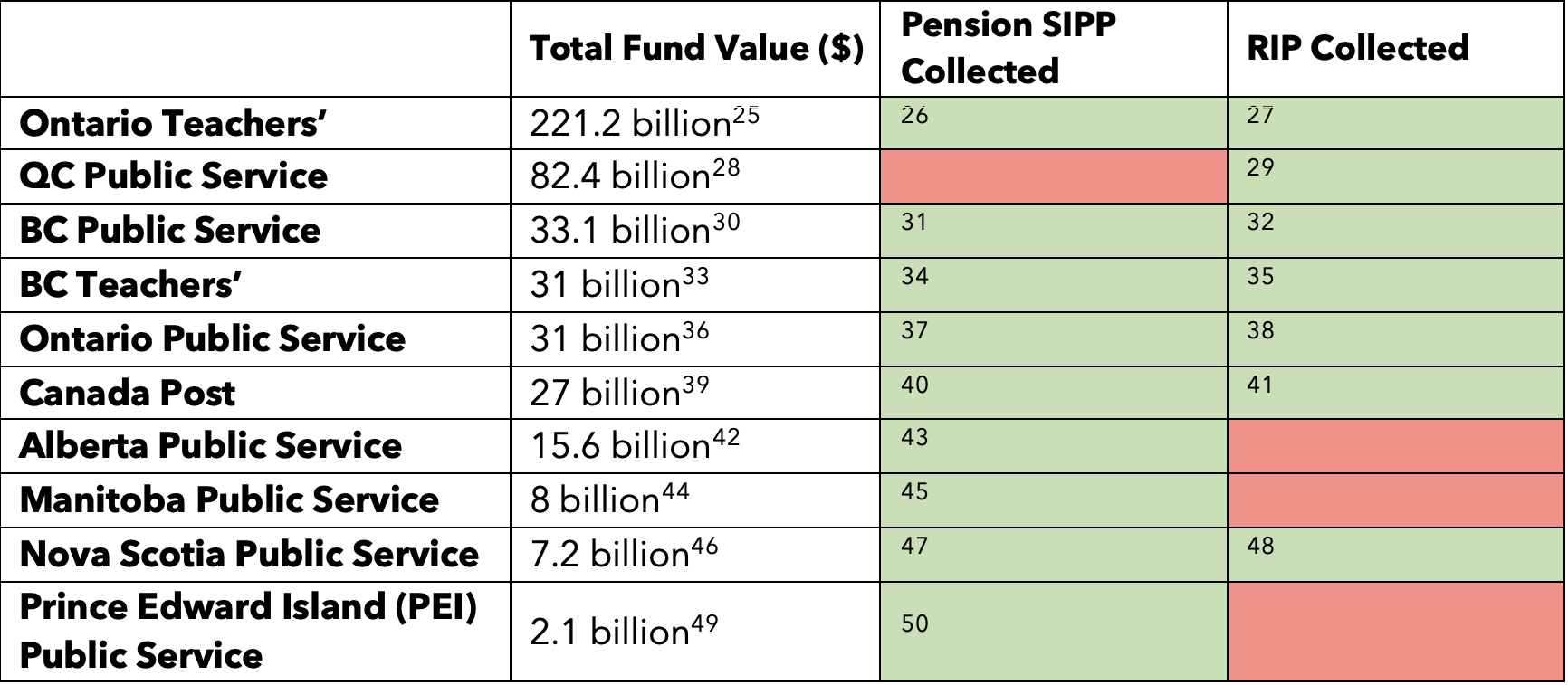

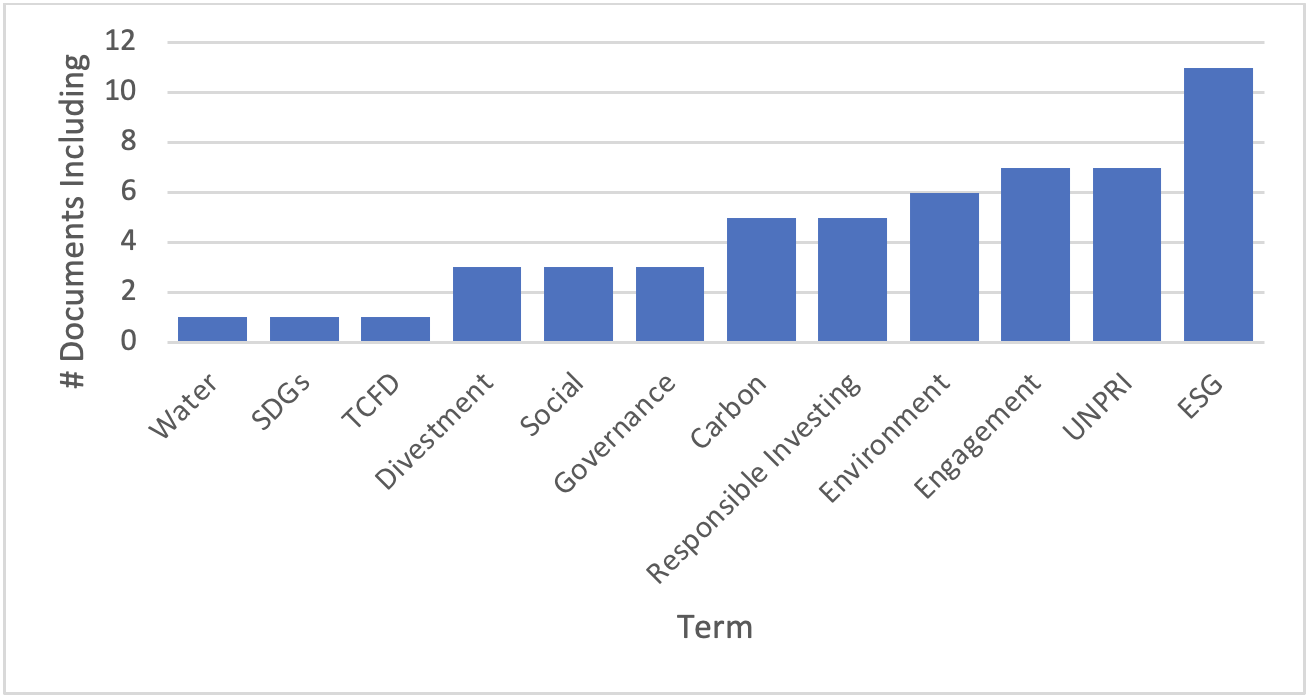

Of “ethics” codes that were cited in the methods section, the following were not included in any SIPP or RIP: climate, equity, food, gambling, Indigenous, land, plastic, poverty, sustainable development and tobacco. Figure 2 highlights total mentions of other “ethics” terms across the various policies. Note, this includes duplicate mentions (i.e., in both SIPPs and RIPs under the same pension plan).

Figure 2: Ethics Terms Inclusion in Investment Policies

Note: SDGs are the UN Sustainable Development Goals and UNPRI refers to the UN Principles for Responsible Development.

Of the 16 policies included, only one document mentioned water60 and the SDGs.61 Of the most common terms, only 11 documents (69 percent) mentioned ESG in their policies, and under half (n=7) reference the UNPRI, either in alignment with the principles or as signatories. As terms were referenced more specifically and therefore required greater commitment in their action, such as ESG and the UNPRI with few mentions such as water, but also those noted above with zero mentions, references in investment policies decreased.

Table 3 below notes term inclusion by individual investment portfolios.

Table 3: RI Term Mentions by Portfolio (Includes Mention in Both SIPP and RIP)

Of the policies that explicitly adopt RI practices, 25 percent of these policies do not mention who is responsible for ensuring that RI policies are integrated, or indeed how this process of RI integration will be monitored. Of the funds that do mention who is responsible for RI integration, all six of the pension plans explicitly delegate their RI to the investment manager, an external professional hired by the portfolio. Of the six policies, only two require RI reporting to the committee by the investment manager.93

RI Delegation in SIPPs and RIPs

Some portfolios claim they prefer RI engagement rather than divestment. This may come from exercising their voting rights, which grant shareholders the ability to contribute to major decisions and could influence sustainability decisions by advocating for responsible business practices. Portfolio policies on voting rights in both SIPPs and RIPs are therefore particularly relevant, as the way that they use voting rights determines their ability to make change. Of the policies analyzed, voting is delegated to the investment manager for eight of the 10 portfolios — that is, investment managers vote on matters taken by the corporations held to the investors in alignment with their policies. However, of the 10 portfolios included for analysis, only three mention voting to advance RI considerations, meaning that RI considerations are not included in voting considerations for 70 percent of the policies analyzed.94

Discussion

To answer the three questions guiding this paper, the discussion is presented in three parts: overall specificity in RI consideration and integration within investment policies of global governance recommendations as required by international best practices; the ability of RI considerations to guide investment actions; and the causes of variation in RI integration. Each section highlights the key issues for policy makers and practitioners on RI considerations in their own policy integration.

Lack of Specificity in Investment Policies

As required by the two guiding international global governance frameworks, as well as federal policy requiring adoption of the TCFD, SIPPs need to be specific about whether and how RI considerations are incorporated into investments. Simply put, this bar is not met by Canadian public pension plans.

With the brevity in overall RI considerations as a percentage of SIPP documents came a lack of specificity in RI integration in SIPPs, as is seen in both total amount of the SIPP committed to RI as well as the mention of specific RI considerations. Compared to recent data on Canadian university pension SIPPs, the Canadian public service pension SIPP average mention of ethics terms and the percentage committed to ESG is less than half, demonstrating that their policies are lagging behind other comparable policies in RI integration.95 Perhaps most interesting, only one portfolio mentioned the TCFD, a policy required by the federal government to be incorporated into crown corporations policies, with mention of either its integration or justification for its exclusion. This points to the fact that national government intervention is not being incorporated into investment policies. Of terms included, broad terms such as ESG and UNPRI were included most often in place of specific terms such as climate or plastic, which serves to further illustrate this point.

This lack of specificity was further reflected in delegation practices. Where RI was delegated by every plan that included RI considerations, only two required that the investment manager report on their RI. Given that engagement was noted as a favourite form of RI in statements, the fact that proxy voting was not mentioned as a tool for RI illustrates an overall lack of commitment to RI in practice, and the overall lack of RI specificity does not lend itself to advocacy towards RI practices in the business held. Added to this, there was a general lack of specificity where RI considerations should have been included, which left much of the decision making up to individual investment managers. While past research has found that investor activism can be successful in promoting RI, utilizing voting rights towards RI objectives is crucial and requires specificity.96

This lack of integration is consistent with past research on RI and, as past studies have identified, could be a result of an overall fear of economic loss as a result of RI97 or may be due to an overall lack of capacity to understand how to integrate RI.98 Regardless, it reflects a failure of Canadian public pension plans to align themselves with recognized global governance frameworks. Overall, this lack of specificity is troubling and requires attention by policy makers.

Lack of Integration of RI Guidance

The lack of specificity in integration demonstrates how some of Canada’s largest pension plans were able to increase their investments in the Canadian oil sands. The fact that only four portfolios mentioned “carbon” and only five mentioned “environment” shows a relatively limited ability of SIPPs and RIPs to prevent such behaviour. This is to say that as these portfolios increase their investment in the oil sands, the lack of codified actionable options, as prescribed by global governance frameworks, allows them the flexibility to change their investment composition without a clear philosophical change. Essentially, the plans’ reinvestment in the oil sands is perfectly in line with their investment policies, because their investment policies do not discuss it in much detail. While the investment policies that increased their investment in the oil sands claimed that they would transition towards RI practices, the lack of specificity in the policy shows a clear break between their public-facing statements and the policies that guide their investment frameworks.99 This is further demonstrated by the fact that a minority of investment portfolios studied, and even a minority of investment portfolios that do mention RI, do not note voting as a method for RI consideration in their polices. The reinvestment in the oil sands may not have been prevented through alignment with Canada’s required TCFD adoption and other global governance frameworks, but increased specificity on how and whether RI is considered would promote greater transparency to the public in the types of investments that are permitted and whether RI is seen as an integral part of the philosophy or a virtue signal. Ultimately, it is the lack of alignment with international and national standards on RI that have allowed for increased investment in the oil sands to be in-line with investment portfolios. Further alignment with international best practices would support greater specificity and alignment with national requirements.

RI Integration Based on Size

Overall, there does not appear to be a geographic correlation for RI variation for public service pension plans in this sample, but rather a relationship based on size. While it might be expected that the western provinces might incorporate RI less, due to their heavy reliance on oil in adoption of geographically informed RI,100 the lack of RI specificity in eastern provinces cannot be explained solely based on a lack of ethical or environmental considerations by province.

While there does not appear to be a correlation between larger funds and greater detail for ESG integration in the SIPP, what is obvious is that the four smallest plans (PEI, Nova Scotia, Manitoba and Alberta) all include the lowest amount of detail on RI integration, both in terms of amount of SIPP committed to RI and to global governance bodies and frameworks, and specific mention of key RI terminology. In fact, these four plans are the only plans that either do not include RI considerations or only include it insofar as it does not conflict with other objectives, without discussing how environment and climate risk may pose a risk on their own. Given the size of their portfolios, as past research has shown, there may be a fear of ESG integration having a greater impact on their portfolio from exit costs or lower returns.101 This is consistent with past literature, which argues against RI for fear of lower returns and therefore a failure to meet the portfolio’s fiduciary duty.102

With the obvious outlier of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan, increasing portfolio size tends to increase specificity in mentions of ethical investing terms. These findings further corroborate the above assertion that RI is incorporated less often in smaller portfolios and more frequently in larger portfolios. This claim is consistent with international studies that have found that larger funds incorporate RI more frequently103 and provides an area for future research, as smaller funds in this sample do not support past findings. This seems to point to the fact that even when integration of global governance policies such as TCFD and UNEP FI was limited, the incorporation of such frameworks increased in this sample with policy size and serves as a challenge to practitioners with smaller portfolios and government agencies to support smaller portfolios in RI integration.

Conclusions and Policy Implications

In this examination of RI integration in a small sample of Canadian public service pension funds, three major findings emerged. First, portfolios included did not broadly adopt international or domestic best practices of RI set by global governance bodies regardless of nationally legislated incorporation. Second, there was a lack of specificity in RI integration, which allowed for investment such as that seen in reinvestment in the oil sands, despite public declarations of RI and divestment. Third, RI specificity tended to increase as portfolio size increased. These findings are consistent with past research that points to a lack of RI integration across investment portfolios and could be due to numerous causes, including a fear of loss of returns and overall lack of capacity to integrate RI.

These findings add the novel contribution to the policy sphere that portfolio size, rather than other factors, may be a key driver in influencing the level of RI integration. Even given the limited overall integration of RI in investment policies, greater portfolio size generally increased the specificity of RI integration, which thus resulted in greater delegation and required action.

This paper adds an important finding that smaller funds are not integrating or even addressing these standardized global governance frameworks and, therefore, their reach is still relatively limited. Where binding policy requiring integration of globally recognized standards has failed, perhaps further education on the benefits and process of RI integration or professional development to help plans understand the financial materiality of RI considerations could serve to increase integration.

A limitation of these findings to consider would be the relatively limited number of investment policies included. While pan-Canadian in its scope, the sample did not include all Canadian public service investment policies, but rather focused on provincial public service pension plans and high-profile pension funds such as the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Fund. Future studies could attempt to include a larger sample of Canadian public investment funds and/or international portfolios to see if size continues to influence RI integration. This could also add to an understanding of what the threshold is for RI integration in pension portfolios. Moreover, while the portfolios in Manitoba and Alberta were among the smaller portfolios, their historical dependence on investments in oil may have been a contributing factor in their lack of RI integration. Future research should explore if growth in portfolio size increases RI integration or if geography plays a more pivotal role. Additionally, future studies could investigate stakeholder activism for a correlation to RI integration in portfolios.

Ultimately, widespread RI integration will be contingent on proving that investing responsibly will yield greater returns for all pension plans regardless of size. Such an achievement will require not just legislation, but further government support and research.