As the world nervously watches the rollout of a ceasefire agreement1 after 15 long months of conflict between Israel and Palestine, hopes of a lasting peace are tentative and fragile. Establishing trust and a sense of mutuality is a goal that has eluded the region and the international community for 75 years. But this long-term goal may have a more pragmatic long-term solution, one founded in economic integration and mutual benefit that could avoid the replication of failed peacebuilding approaches of the past. An economic corridor through Gaza, as part of a geo-strategic initiative rooted in common economic interests, could become a gradual pathway for peace, productivity and stability in the region. This initiative — the India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC) — offers a credible prospect for delivering sustained economic growth and an equitable quality of life for the citizens of Israel and Gaza alike.

Since the brutal invasion of Israel by Hamas on October 7, 2023, the war in Gaza has incurred unthinkable human costs and destroyed most functional infrastructure. According to the World Bank, Gaza’s education sector has collapsed, while the health sector has been significantly compromised, with most hospitals out of service. The economic situation is catastrophic, with an 86 percent contraction in the first quarter of 2024, displacement of close to two million citizens, and the cost of basic commodities rising by 250 percent since the beginning of the war.2 The multi-phase ceasefire agreement calls for a three- to five-year reconstruction project to begin in its final phase, after all remaining Israeli hostages have been released and Israeli troops have withdrawn from the territory. The clearing of rubble and eventual rebuilding of homes and commercial buildings will require vast sums, as well as the ability to bring construction materials and heavy equipment into Gaza. Estimates (from mid- to late 2024) of the cost to rebuild Gaza range from US$40 billion3 to US$80 billion.4

While the international community has been engaged through the UN Security Council, the International Court of Justice and other international organizations, calls have been made for these bodies to act together to foster a rules-based international order that is grounded in the principles of justice and accountability for the alleged crimes committed, and to extend assurances to both Israelis and Palestinians of their security, independence, economic stability and a better future. This international engagement has also set in motion an urgent global discussion to determine what will follow “the day after” the fighting ends.5 However, an intense focus on the near term increases the risk of once again leaving long-term problems unresolved. The historical record of the aftermath of previous Middle East peace agreements amply demonstrates that diplomacy alone will not be sufficient for a lasting peace. Gradually evolving Gaza into a global trading hub between Europe and the Far East could provide sufficient incentives for shared, broad-based economic opportunities and benefits for Israelis, Palestinians and the global community that can serve as a foundation for regional peace.

The Regional Economic Potential of IMEC

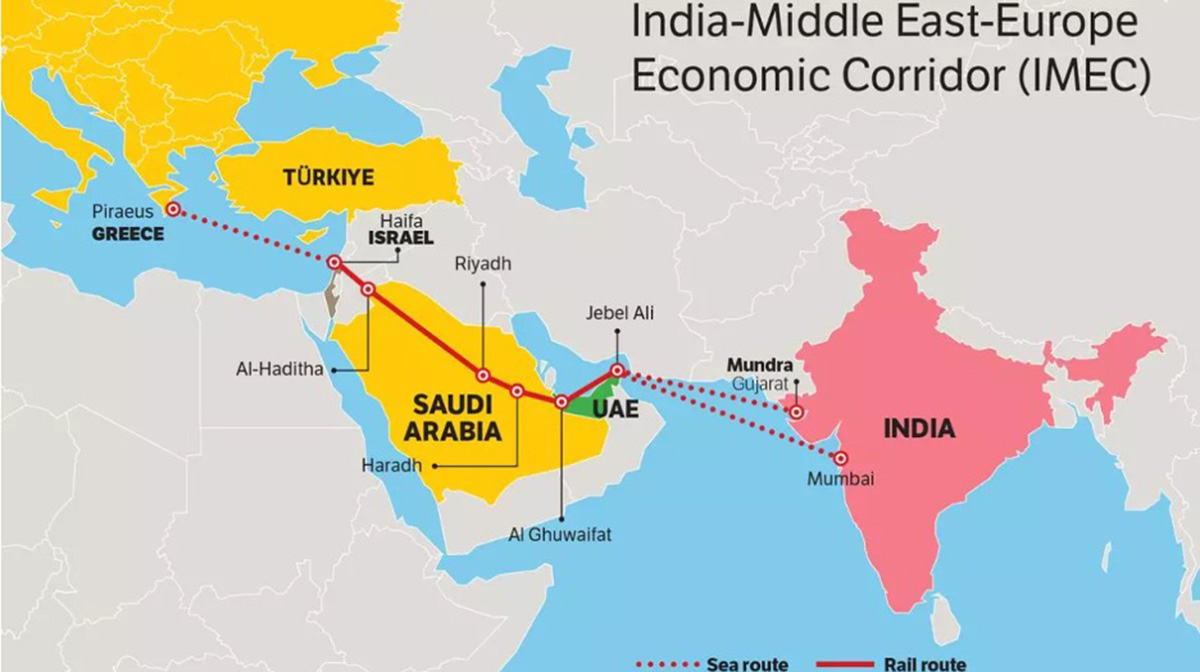

The IMEC initiative, announced during the G20 Summit in September 2023, could play a crucial role in establishing a connection between Asia and Europe via the Middle East.6 The countries involved include India, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), France, Germany and Italy. Although the United States is not directly involved in the corridor, it is a key partner, given how IMEC could support its strategic interests in de-risking the impact of Chinese economic and security policies and in reducing its European allies’ dependency on Russia.7 The potential regional and global economic benefits of this corridor are widely documented.8 IMEC is a project aimed at building and strengthening the connectivity between India, the Arabian Gulf and Europe. Several key features of the project include: railway lines to complement existing maritime and road transport routes; development of high-voltage transmission capacity for clean electricity transfer; clean energy pipelines across a vast region; and next-generation digital connectivity. Apart from being an ambitious project with significant economic potential, the most striking feature of the project is its ambition to enable enhanced and robust connectivity between India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel and Europe. By creating incentives for, and stakeholders in, transformative technology-enabled economic integration, IMEC has the potential to provide a critical missing ingredient in resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict: the foundation for an integrated regional economy that delivers tangible benefits to all partners.

The IMEC corridor’s strategic significance lies in its ability to provide cost-effective cross-border transportation networks, employing ship-to-rail connections. These connections would complement existing maritime routes and promise both a 40 percent reduction in transportation time and a 30 percent decrease in costs.9 Its aims include boosting efficiency, enhancing regional cooperation, strengthening regional supply chain resilience, reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and, with the integration of fibre optic connectivity, elevating digital transformation across the region (see Map 1). Serving as a bridge between the green and digital landscapes, and boosting the resilience and efficiency of supply chains, the corridor could facilitate the export of clean energy through hydrogen gas and promote interconnectedness within power, gas and telecommunications networks. These operational networks would have the potential to facilitate a historical transformation across all sectors. The project would not only connect Asia through the Middle East to Europe but could also foster “normalization” between Saudi Arabia and Israel.

Map 1: Original IMEC Plan

Source: Frontline

Challenges and Constraints

These benefits notwithstanding, IMEC’s stakeholders are cognizant of the impacts of the conflict in Gaza and share concerns regarding a longer-term conflict expanding beyond Gaza.10 Reports of degrading command structures of non-state armed forces exist in parallel with fears that incursions into countries such as Lebanon risk further empowering groups such as Hamas and Hezbollah within their own population centres. The conflict has already put IMEC on the shelf, where it may stay indefinitely.11

Beyond the current conflict in Gaza, the broader political instability in the Middle East is a complex web of historical grievances, national and subnational animosities, and shifting alliances over a vast geographical area. The Middle East and Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) region faces a range of ongoing security threats, including armed struggles, economic and political challenges and territorial-based conflict and instability. These conflicts include the Indo-Pakistan dispute, a multifaceted conflict fuelled by Chinese influence in Pakistan through China’s Belt and Road Initiative.12 Ongoing conflicts in Yemen, Syria, Iraq and Sudan also pose risks to the infrastructure and trade routes. The historical rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran, which could threaten the corridor’s safety, and hostilities between Israel and Lebanon/Iran, pose further challenges. IMEC — or any similar infrastructure development proposal — faces significant threats from political turbulence and the vagaries of internal political forces within the region. IMEC partners need to address other challenges as well, such as logistical challenges related to the need for transportation network infrastructure that is integrated efficiently among many countries, the harmonization of regulatory frameworks, and adequate funding.13 Yet, in spite of these deep uncertainties and challenges, the proposal’s merit is its collective recognition of mutual benefit for national and regional interests. Beneath the surface of current drivers of hostilities, a deeper anchoring of the basis for an improved life quality could, over time, become the determinant of a sustainable peace.

IMEC’s Strategic Importance

In a time when other maritime corridors such as the Red Sea and the Strait of Hormuz face disruption, the IMEC project and its transformative, transboundary nature is attracting praise from global leaders.14 The corridor would integrate two continents with a combined GDP of almost half the world’s total GDP. The genesis of IMEC sought to improve global trade linkages, reduce transportation costs and diversify supply chains. The improved global connectivity envisions electrical grids, digital networks and pipelines for green hydrogen, in addition to the provision of classical trade routes.15 IMEC plans include an eastern link connecting India to the GCC countries, and a northern link connecting the GCC to Europe. The corridor has the potential to encompass economic, political and strategic interests that could significantly impact the landscape of the global economy. It could also deepen physical connectivity across the region, including power, data and logistics, thereby unlocking tremendous commercial opportunities. Potential also exists in cutting the cost and increasing the speed of cargo shipping, providing a secure, high-speed data pipeline that will facilitate global connectivity, and serving as an international green transit corridor linking Asia to Europe.

India, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Europe and the United States all stand to reap benefits from IMEC, including diversified trade opportunities, decreased transportation costs, and strengthened economic and diplomatic relations. For India, the US sanctions against Russia and Iran, China’s growing influence on Central Asia, and competing regional corridors all indicate that India requires more cost-effective and expeditious ways of trading with Europe, the Middle East and North America.16

Both Saudi Arabia and the UAE are seeking to diversify their economies from a dependence on fossil fuels.17 The corridor could allow them to do so by facilitating increased trade volumes and by providing links to electrical grids via IMEC’s proposed undersea cable.18 Improved connectivity would complement the heavy investments by Saudi Arabia and the UAE in upgrading their ports and the GCC railway network, expected to be completed by 2030.19

Europe could also be a leading beneficiary of IMEC through increased trade and export access. This access is essential, considering the challenges associated with an increasingly protectionist posture by the United States, the need to diversify gas imports during a time when public investment opportunities are constrained by a waning economy, and Europe’s current dependency on Chinese goods and Russian fossil fuels.20 Moreover, Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s significant investments in India’s agricultural sector could further support the food security of the GCC countries.21 Finally, IMEC would allow Europe to develop closer economic ties with other involved parties, thus enhancing Europe’s geopolitical influence in the Middle East and South Asia.22,23

Finally, although the United States is not directly involved in the corridor, it is considered one of the project’s driving forces.24 Beyond obvious attractions such as strategic influence and economic benefits, the United States has an interest in regaining some control and influence over key geographic areas lost to other countries.25 The IMEC corridor could support more stable energy supply routes from the Middle East to Europe, and potentially to India, contributing to global stability and predictable energy prices. America’s continued support for the Abraham Accords,26 and its pursuit of stronger diplomatic relations between Israel and Saudi Arabia, are also significant.

US President Donald Trump has made it clear that peace in the Middle East is among the early priorities of his second administration. His previous administration made it a priority to disrupt America’s enemies in the region and to build a coalition of allies through the Abraham Accords.27 As with his previous presidency, Trump’s current term is likely to heavily benefit Gulf states who understand his transactional approach.

Challenges Facing IMEC and Competing Options

The proposed IMEC corridor is in a complex geopolitical region. Its development has been affected by ongoing Israeli-Palestinian tensions and the war in Gaza in particular. The Memorandum of Understanding on the Principles of an India-Middle East-Europe Economic Corridor, signed on September 9, 2023, stipulated that IMEC partners would formulate a full plan for the development of the corridor within 60 days.28 More than 16 months have elapsed since the declaration was signed, without any progress being made toward the plan’s execution. In parallel to this, discussions between Saudi Arabia and the US administration to conclude the normalization of relations between Saudi Arabia and Israel were halted, based on Saudi Arabia’s argument that normalization would need to be predicated on the resolution of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and the establishment of a Palestinian state, adhering to its 1967 borders.29

Several IMEC members, namely Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Israel, are currently deeply intertwined with China. Saudi Arabia has the Comprehensive Strategic Partnership, which has been key to diversifying its exports away from oil. The UAE acts as a doorway to the rest of the Middle East, Africa and Europe, facilitating more than 60 percent of Chinese imports to re-export into these regions, and is dependent on China for its nuclear program. Israel participates in China’s Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, rather than the US-led Asian Development Bank, which has been rewarded with considerable infrastructure investments.30 These ties run deep, as the Gulf states trade much more with China than with Europe, and significantly more with China than with the United States.31 However, trade with Europe is significantly more diverse than with China. China also has important infrastructure investments throughout the route, owning two-thirds of Greece’s Port of Piraeus (the European entryway for the corridor) and 20 percent of Saudi Arabia’s largest port, the Red Sea Gateway Terminal.32

Egypt, a key player in the Middle East and North Africa region and with strong ties to IMEC partners (the United States, the UAE and Saudi Arabia), has voiced reservations toward the project. Egypt considers IMEC an alternative corridor, rather than a complementary one, to the Suez Canal, which supplies Egypt with a major source of foreign currency. Egypt is already facing major economic challenges: soaring levels of public debt, the Red Sea security crisis,33 and a significant influx of refugees from both Sudan and Gaza,34 have combined with the geopolitical stressors felt from Russia’s war in Ukraine. The war in Gaza has also led to a drop in tourism in Egypt and has contributed to a 50 percent decrease in receipts from economic activity in the Suez waterway.35 Egypt’s engagement with IMEC remains critical to securing a smooth execution of the project. This is especially important as, based on China-Europe Railway Express numbers, the Suez Canal is likely to remain a cheaper option than IMEC to bring goods from Asia to Europe.36 However, the capacity limit of the Suez Canal and the recent attacks on it will likely attract transporters to IMEC.37

Turkey’s interest in seeing IMEC pass through its territory was made clear in a statement by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan that there would be “no corridor without Turkey.”38 Turkey sees the potential of IMEC as a gateway for global trade, serving almost half the global GDP. And, with its geo-strategic position straddling Europe and the Middle East, Turkey is keen to play a major role in hosting IMEC’s development. The fact that the Iraq Development Road Initiative, a highway and railway corridor stretching 1,200 kilometres from the city of Basra to the Turkish port of Mersin, initiated by Turkey, is also facing challenges due to instability in Iraq, as well as from Turkey’s ongoing conflict with its Kurdish population, serves as further incentive for Turkey to become a major IMEC stakeholder. This said, some see Turkey’s involvement in the Iraq Development Road Initiative, and its current absence from IMEC, as a sign it remains hesitant toward the initiative.39

Beyond national level concerns, a number of transboundary issues surrounding the practicalities of executing the IMEC project also persist. The project requires a significant funding commitment from national governments, international financial institutions and the private sector. As the proposed corridor encompasses major infrastructure elements, including building ports, railroads, electrical grids, logistical and handling facilities, issues need to be addressed such as customer services, border-crossing procedures and transportation systems. The corridor’s proposed route through multiple and diverse regulatory frameworks and economic regimes requires careful navigation, as these systems will rely on technology applications for which global governance and regulatory frameworks are currently lacking. The harmonization of frameworks, systems and processes is critical to facilitate trade, movement of labour, and cross-border investments among the participating countries, particularly as some partner countries may adopt protectionist policies to preserve local industries.40

IMEC and the Conflict in Gaza

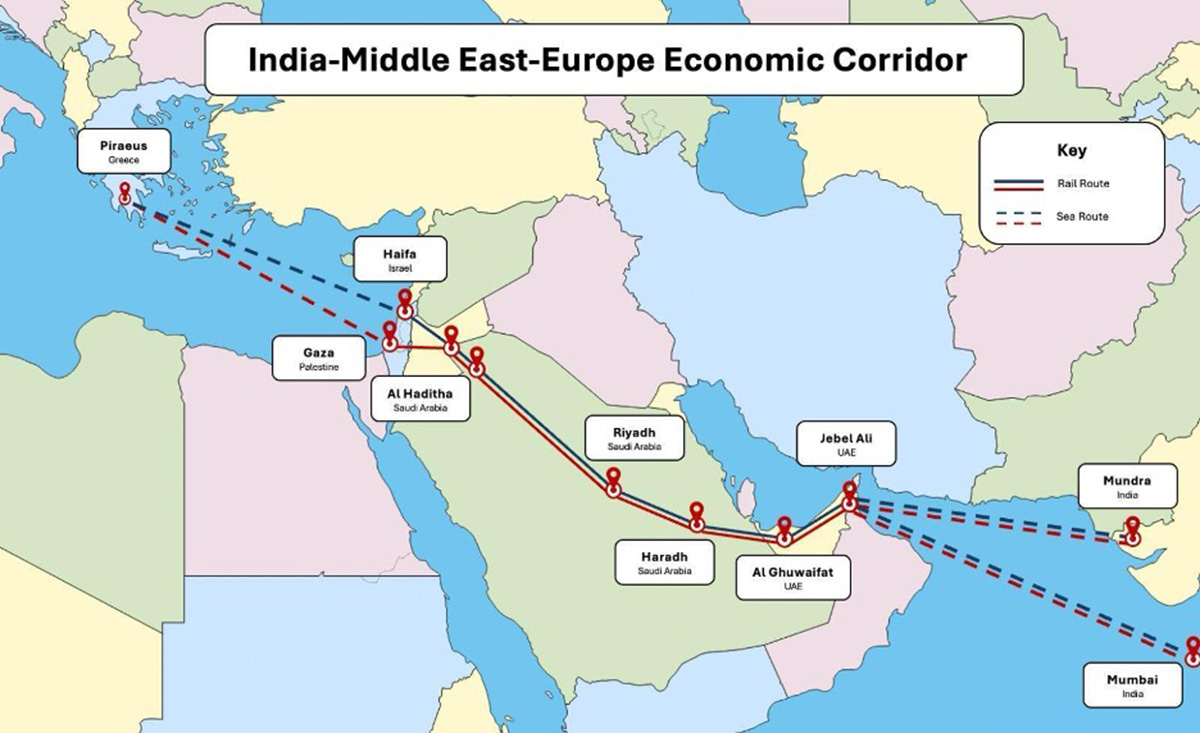

With Gaza’s infrastructure destroyed, and an unaffordable reconstruction bill looming, integrating the Gaza Strip into IMEC could bring about a collective responsibility from the international community to compensate for the infrastructural loss and help stabilize the territory economically and politically while also addressing broader security concerns. This would not only secure funding for Gaza’s reconstruction but would also embed IMEC within the region (see Map 2). The construction of a new, state-of-the-art port in Gaza would naturally lead to the rebuilding of Gaza’s infrastructure, generate tens of thousands of jobs, and stimulate Gaza’s economy. The impact of these infrastructural developments could contribute not only to the resolution of the longstanding conflict, but also to Gaza’s enduring social and economic challenges, marked by one of the world’s highest unemployment rates.41 It would expose Gaza’s population to the global economy, and open new opportunities, apart from aid or militancy.

Map 2: Revised IMEC Plan, Integrating Gaza

Potential Regional and Global Impacts of Integrating Gaza into IMEC

Previous initiatives that considered an economic-based approach to resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict have not gained traction due to their failure to address the core political issues of the conflict. These include disputes over borders, refugees and sovereignty. Additionally, without a mutual and genuine commitment to negotiate and compromise, driven by an active engagement from the global community, economics alone may lack the necessary support to end such a long conflict.42 Yet, post-conflict reconstruction is the key topic on the table. Rebuilding infrastructure will create jobs, stimulate economic growth, and help address the grievances that, if not addressed, will lead to renewed violence.

The world has witnessed many situations where economics had a direct impact on resolving conflict.43 These include the case of Rwanda, in which the post-genocide recovery focused on economic growth, reconciliation and governance reform that helped stabilize the country.44 Bosnia and Herzegovina is another well-known case that shows how post-conflict economic development played a vital role in rebuilding the country and promoting peace.45 In both cases, as well as other cases such as Northern Ireland, foreign investment and job creation improved living standards and reduced the appeal of violence.46 Although not every attempt has succeeded,47 economic peacebuilding remains an imperfect but important tool.

A key reason that economic aid has failed to end the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in the past is that economic interventions, often limited in scope, were implemented at the local level or as part of bilateral negotiations between Israeli and Palestinian authorities, without wider regional or global interconnections. Such interventions also proved to be insufficient due to political factors being weighed more heavily than economic interests, by both parties, in many situations. Additionally, the failure of economic intervention has had a negative impact only on the Palestinian side, with no wider negative impact on the region or on global players. Using Gaza’s integration into IMEC as a Middle East peacebuilding enabler will support the stability and prosperity of both Gaza and the West Bank as essential for achieving long-term peace through global interdependence. A durable peace between Israel and Palestine, as well as in the Muslim world at large, will become a global interest, with the support of the global community.

This integration will lead to having two ports on the east side of the Mediterranean: Haifa in Israel and a new port in Gaza. This will also lead to integrating ports in the Mediterranean, the Red Sea, the Arabian Gulf and European ports, as well as the economic integration of Israel with the wider Middle East and North Africa region. The region would have a global impact by unleashing a wave of technological collaboration in clean energy, carbon emissions reduction and transformative technologies. This integration would not only foster innovation but would also mitigate the long-standing threats of radicalization that have drained the region’s resources for decades.

Toward a Future of Diminished Hostility

The reconstruction of the physical infrastructure in Gaza is a necessary step to restore the quality of life for the people of Gaza. A large investment by global commercial entities in the transportation, telecommunication and energy sectors, followed by swift activity to attract investment to spur long-term economic development, could become an antidote to violent outbursts and the settling of historical grievances. As security requirements in the region become assured, and as Gaza is transformed into a global hub for trade and commerce between India, the Middle East and Europe, the primary forces driving the conflict will attenuate over time.

To facilitate the necessary pre-conditions to execute this somewhat novel peacebuilding project, a stable, long-term ceasefire must be maintained. An interim period to support trust-building, as well as a clear global commitment to the final status settlement, is crucial in reaching a negotiated settlement between parties that fear and distrust each other. The establishment of a unified, empowered, transparent entity that has the trust of both the Israeli people and the Palestinian people, as well as the international community, with interim security arrangements under the auspices of a UN force to help establish the essential security assurances for all parties, must be facilitated.

Once formal acknowledgement is given to the fact that the region is home to both Jewish and Palestinian people, the evolution of legitimate governance processes could become feasible within the scope of a UN mandate. Slow but measured progress toward democratic choices of leadership in both Israel and Palestine — devoid of extreme ideological positions — should be part of the political discourse. Over time, perhaps three generations or more, peace and stability will shape a new reality more aligned with a collective interest: that is, a resilient infrastructure in support of global trade and an improved quality of life for all people in the region.

Several think tanks and foundations have proposed scenarios on what follows immediately after this conflict ends.48 Such scenarios focus on setting up a new government or entity that controls Gaza, and propose the creation of a council of Gazans without linkages to the West Bank (which is also facing challenges). They also focus on the security aspect, with different proposals for “imposing” security inside the Gaza Strip. The plans promise economic prosperity, with no clear enabler to facilitate this beyond indications that GCC countries will cover the cost,49 without presenting convincing arguments as to why the GCC countries should or will do so.50 After previous rounds of conflict between Israel and Gaza, commitments to rebuild Gaza were never entirely fulfilled. Today, as in the past, donors and the key GCC countries want to be confident there will be no future rounds of confrontation. It is also important that these plans accommodate views and input from Palestinians, which they currently fall short of doing.51 For example, the Atlantic Council and Rockefeller Foundation have proposed the establishment of a council in Gaza, which would appoint a multinational authority to take over the mandate for Gaza for an interim period.52

Integrating IMEC into the peace plan for Gaza and the region53 would act as a re-set and a break from the past, taking a fresh approach to the key challenges that have not been addressed and that have perpetuated conflict in the Middle East over several decades. The complexity and risks associated with ongoing conflict, amplified by animosities, shifting alliances and the spread of conflict to the regional, national and sub-national levels, can only be limited through positive economic and political change. Key building blocks are employment opportunities, the reduction of logistical challenges, the harmonization of regulatory frameworks and the resolution of financing challenges to shape a regional infrastructure plan that is integral to the reconstruction of Gaza. Economic development could help alleviate one of the world’s highest unemployment rates and enhance cooperation across the region by spurring a rapprochement between Israel and Palestine, thereby removing the most significant obstacle to peace between Israel and the Arab and Muslim world. Integrating Gaza into IMEC will elevate a level of global responsibility and interest in having stability in the region, as well as addressing the global demand for a “revitalized authority” to lead the governance of Palestine. Due to the heavy investments and multinational corporate engagement involved, the integration of Gaza into IMEC will require a transparent, reliable, professional and capable Palestinian entity that can comply with its global and regional obligations. It will also make the stability and prevention of any future confrontation a global responsibility, due to the vested interests of IMEC partners. This approach seeks to derive enduring peacebuilding gains, such as those seen in Northern Ireland, Rwanda and Bosnia-Herzegovina. It is also inspired by the European Coal and Steel Community, which charted the path, after World War II, to ending centuries of conflict in Western Europe.

A resolution to the Israel-Palestine conflict has proven to be elusive for the past 75 years. On the cusp of that resolution, an alternative vision is the IMEC project, which offers an infrastructural and engineered approach to a lasting peace. By placing Gaza within a geo-strategic focal point of global trade and economic cooperation, this project stands to greatly benefit Israel and Palestine, the wider Middle East region, and the global community for decades to come.