Introduction

In 2017, Canada unveiled its self-proclaimed “world’s first artificial intelligence strategy.”1 In the eight years since, companies from the United States,2 China3 and, to a lesser extent, Europe,4 have dominated headlines in artificial intelligence (AI).5 Meanwhile, Canadian researchers have won both a Nobel Prize and a Turing Award for their foundational contributions to AI.6 Canada used to be recognized as a vibrant AI hub; it is no longer.7 What explains this shift between Canadian contributions to the emergence of the field and its current technological deployment? Is Canada falling behind, or is this merely a media blind spot? Utilizing patent data, this paper will attempt to show a portrait of the world’s AI patent landscape and explain what happened to Canada’s apparent lead in the field. It will build upon methodology from previous reports to collect patent data, then identify current trends in cross-border AI patenting ownershipi flows, to finally evaluate the adequacy of current Canadian policy and chart a path forward, a path informed by a digital economy where knowledge rents reign supreme and wages stagnate.8

Approach and Method

This project builds upon the World Intellectual Property Office (WIPO) Patent Landscape Report on Generative AI9 and the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI) AI Index Annual Report.10 Both propose a comprehensive methodology for identifying AI patents, with slightly different definitions. The WIPO approach, being a historical analysis, casts a much wider net by including technologies and concepts that are foundational to AI, such as “Random forest [models]” and “Bayesian networks.” Merging both lists (see Appendix 1) yields the broadest definition of AI, which allows for the most comprehensive profile of countries’ AI activity. This list was then used as a search string for Questel’s Orbit Intelligence patent family (FamPat) database.11 This database compiles data from worldwide patent offices, minimizing the impact of regulatory discrepancies across patent jurisdictions.

Patent count is used to measure AI innovation and production because it can easily be measured and provides quantifiable results, simplifying comparison, and because it is generally representative of the broader innovation landscape. Indeed, economists have repeatedly shown that patent count is an accurate proxy for broader innovation.12 Furthermore, in the case of AI, the Stanford HAI report has repeatedly confirmed that patents are generally correlated with academic papers and open-source projects on GitHub. Patents are not simply a proxy, but the quantifiable output of the innovation process. Patents are the tip of the innovation iceberg, with the bulk of knowledge — proprietary algorithms, techniques and data, custom code and trade secrets — remaining hidden within a corporation’s black box.

Patenting also acts as a consolidating force, limiting the ability of emerging players to compete and innovate by locking them out of foundational technologies or forcing them to pay rents to participate.13

This study focuses on six countries and one region: Canada, China, the European Union (EU-27), Japan, South Korea, the United Kingdom and the United States. Collectively, these seven jurisdictions account for more than 98 percent of all AI patents. The study includes data for the last 20 years, starting in January 2005. The cutoff date of December 2023 is due to data unreliability caused by delays in patent processing and database updates. While attempts have been made to forecast more recent patent data, those results inherently remain consistent with existing data and thus would not modify the conclusion.14 Nevertheless, the long study period allows for historical comparisons by capturing the vast majority of the history of AI as a commercial product. For the purpose of this paper, “assignee” refers to the owner of a patent, generally the corporation commercializing the product; “inventor” refers to the person or persons listed as the inventor on a patent, generally the individuals who came up with the invention; “parent company” refers to the owning company of an assignee (e.g., Alphabet Inc. for Google); and dates refer to first publication date (except for Figure 1).ii

The database provides “parent company” only as an output, not a variable, and does not otherwise differentiate between parent company and subsidiary for the assignee country variable. This means that, for example, Google and Google Canada are two different companies in the database, with the first being “headquartered” in the United States while the second is headquartered in Canada. This means that if Google Canada is listed as the assignee on a patent application, the database considers that patent to be Canadian. For the purpose of understanding patent control, this would be inaccurate. Therefore, the output was adjusted: for each country, the top 100 assignees were analyzed, and subsidiaries were reassigned to their parent companies’ country as appropriate. These 100 assignees represent around 50 percent of the patent set for each year (see Appendix 2).

Findings

As found in previous studies on this topic, AI patent registration has had a major, quasi-exponential increase over the early 21st century (see Figure 1). From 2005 to 2023, 5,793,128 AI patent applications have been filed, and 2,734,220 patents have been granted. The rise of patenting corresponds to the evolution of the technology, as it has matured greatly during the period: its economic benefits have been made clearer,15 and funding, from both the government and the private sector, has increased considerably.16 This continuing trend underscores the reality that countries, notably Canada, may be quickly left behind by a tidal wave of innovation ownership. Given that it is possible to go from the cutting edge to the tail within months, it is necessary that Canada carve out its ownership stake in the ecosystem to ensure economic benefits, but also to guarantee that it has the leverage required to shape — or at the very least meaningfully contribute to — global AI policy.

Figure 1: Number of AI Patent Grants and Applications, 2005–2023

Source: Authors.

Note: While appearances may suggest that the gap between applications and grants is widening, the ratio has consistently remained between 40% and 60%

Subdividing the data into the jurisdictions of interest highlights three categories of patent assignees as of the 2020s: (1) the “Underperformers,” firms from Canada, the European Union and Great Britain, owning less than 75 patents per million people; (2) the “Proficient,” firms from the United States, China and Japan, owning less than 300 patents per million; and (3) the “Elite,” firms from Korea, owning almost a thousand patents per million people (see Figure 2).

These groups are also defined by their growth. The Proficient and Underperformer groups have slowly increased their ownership over the last 20 years, while the Elite group’s ownership skyrocketed over the last decade. The performance of the Elite group is mostly explained by these countries’ ability to capture global inventorship. Korea’s inventorship has grown slightly less than threefold, in pace with the other countries’ average increase, if slightly slower. This gap between inventorship and ownership suggests successful patriation.

While per capita figures provide useful comparability, the total number of patents held also matters greatly (see Table 1). While it should be taken with a grain of salt — Canada’s 40 million people are unlikely to match China’s billion — the extremely skewed ownership poses a very real barrier to entry. By cornering the patent market, China and the United States can wall out innovators and ensure they benefit from all innovation, as any technology built on their patents could be either blocked or involve rent payments.17 Figure 3 clearly displays this capture, while highlighting that it remained limited before the mid-2010s.

As for Canada, a noticeable uptick in inventorship away from its group happened around 2017 (see Figure 4). The year is particularly notable as it coincides with the release of the so-called National Artificial Intelligence Strategy. This may suggest that the policy has been particularly effective at increasing the country’s inventorship. However, the growth in inventorship is not mirrored by a growth in ownership. As will be discussed later, the emphasis on patent production of this policy leaves Canada lagging behind Chinaiii and Korea. Notably, while patent invention increased by around 40 percent between 2018 and 2023, ownership increased by only 20 percent. Overall, this is a positive trend and, if it continues, Canada’s inventorship is on track to catch up to that of the United States and Japan, bringing it within the top three by the late 2020s. But without a proportionate increase in ownership, the economic impact will be lost.

Figure 2: Number of Assigned AI Patents, per million people, by country, 2005–2023

Source: Authors.

Table 1: Sum of Live AI Patents Granted, by country, 2005–2023

| China | USA | Japan | South Korea | EU-27 | UK | Canada | |

| Assigned | 1,071,011 | 313,071 | 147,128 | 139,073 | 101,241 | 14,024 | 12,598 |

| Invented | N/Aiii | 302,398 | 140,185 | 83,193 | 114,782 | 22,751 | 21,120 |

| Retention Percent | N/A | 104% | 105% | 167% | 88% | 62% | 60% |

Figure 3: Number of Assigned AI Patents, by country, 2005–2023

Source: Authors.

Figure 4: Number of Invented AI Patents, per million people, by country, 2005–2023

Source: Authors.

Figure 6 gives a much clearer demonstration of the quickly improving performance of Korea: it towers above the others in patent attraction and capture. Patent attraction is measured through the flow of patent ownership from inventor to assignee. It is calculated using Equation 1, where a is the number of patents assigned to corporations in a country and i is the number of patents invented within a country, based on inventor address.

It provides an overview of how successful countries are in both retaining their innovation and in patriating foreign inventions. A country-year with a value of -5 loses five patents for every 10 it invents, forfeiting half of its patents, whereas a country-year with a value of 5 registers 15 patents for every 10 it invents, attracting 30 percent of its patents. Korea is the breakaway winner in patent attraction, while it used to sit with the underperformers (leaking 40 percent of its patents); it has completely reversed the situation, now tripling its patent ownership through attraction, accounting for 80 percent of its growth. Beyond Korea, Japan and the United States are the other countries that have successfully inverted the trend by transforming their patent leak into a patent funnel, although with a much more moderate outcome. In contrast, Canada has been consistently registering fewer patents than it invents, losing around fifty percent of its patents in 2023.

A possible explanation for this gap in ability to attract patents is the presence of extremely large corporations within China’s and Korea’s ecosystems. Combined, Tencent, Huawei, the SGCC and Baidu account for 5.8 percent of all patents published in 2022, more than Canada, the United Kingdom, and the European Union (or Japan) combined. Similarly, Samsung, with 1.7 percent of all patents, owns half as many patents as the entire European Union (or Japan). Such large companies have offices around the world and extract value from the best and brightest from every country, patriating all their inventions and discoveries back to the firm’s home country, along with the revenue and economic impact these provide. Figure 7 provides a glimpse into this reality. Despite Chinese companies accounting for only 57 percent of patent assignments, they account for 70 percent of the top companies. The figure also showcases the dominance of a few players: taken together, these 98 companies account for more than 30 percent of the year’s patents. The figure also closely mirrors Figure 6, supporting the idea that large companies, either through their global network of research centres or through a critical mass of capital, are exponentially more successful in capturing patent ownership.

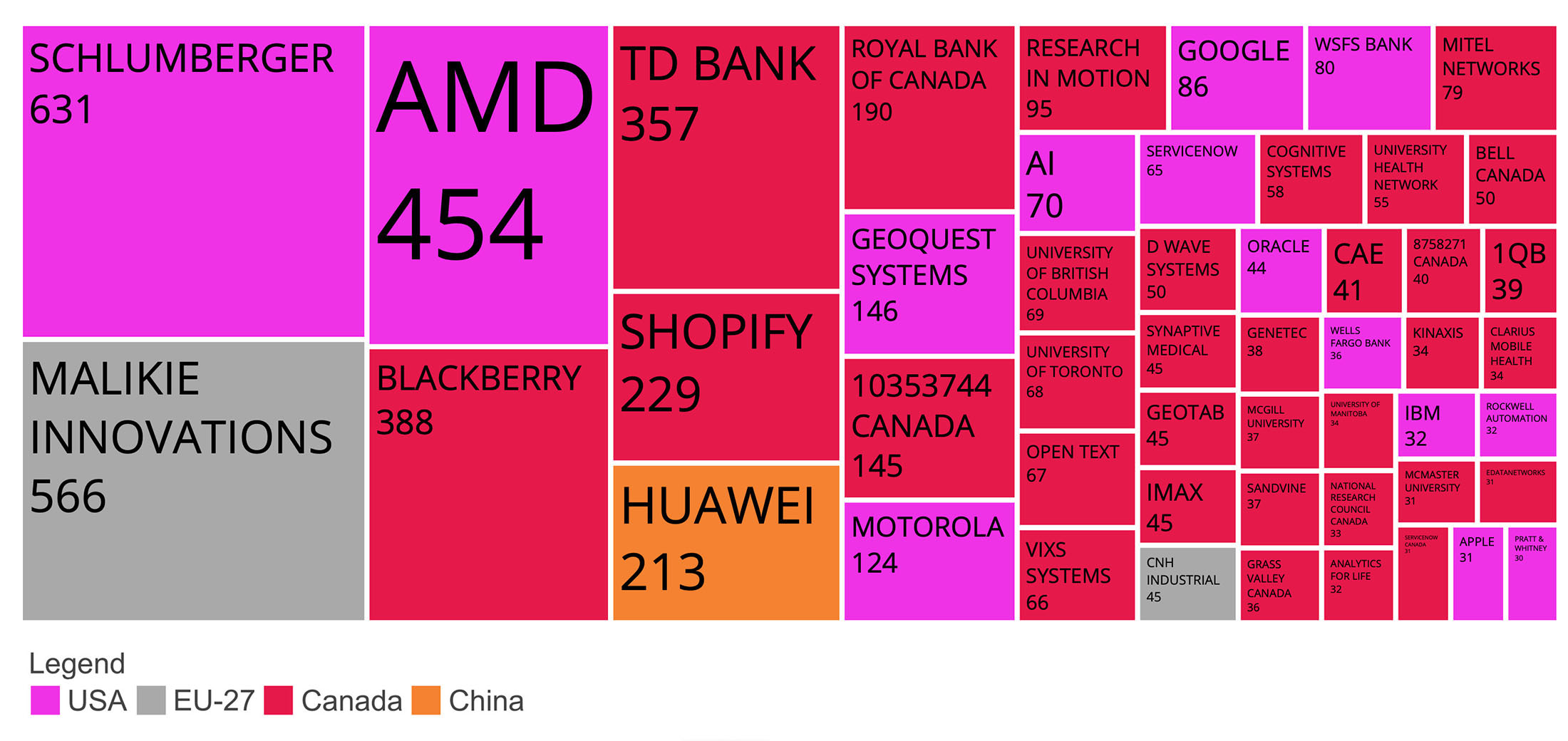

This has major implications for Canada, as the country lacks any dominant AI player. In fact, the top 10 most important patent assignees affiliated with Canada include four foreign corporations, notably Huawei, a Chinese company that mostly operates R&D offices in Canada,18 thus patriating both profits and knowledge back to China. The first assignee, Schlumberger, is an American oil company, extracting both intellectual and physical property from Canada. This is a perfect display of the continued trend of Canada as a producer of inputs, capturing none of the profits from the value chain. Similarly, the second assignee, Malikie Innovations, a patent aggregator and owner of most of the early Blackberry patents, exemplifies the failure of the country to maintain its ownership over inventions of even its most successful firms. Compounding this, despite having a historically significant automotive industry — an industry that produces a large number of AI patents — no major producers are headquartered in Canada, and therefore none of the patents developed by Hyundai, Kia, Toyota or Volkswagen will accrue benefit to the country.

Figure 5: Top 50 Canadian-affiliated Assignees by Sum of Live AI Patents Published, 2005–2023

Source: Authors.

Figure 6: AI Patent Ownership Retention and Attraction, by country, 2005–2022

Source: Authors.

Note: This figure shows the rate at which a country either attracts or leaks patents, in relation to the number of patents it invents. A value of 20% indicates that it attracts 20% more patents than it invents; a value of -20% indicates that it loses 20% of the patents it invents.

Figure 7: Top 98 Firms, by Share of 2022 AI Patent Publication, by country

Source: Authors.

Note: Some names were shortened for simplicity and readability; some companies were merged due to improper parent company categorization, thus 98 firms are shown instead of 100.

Implications and Importance of Domestic IP Capture

The previous figures provide a plethora of statistics where Canada presents poorly when compared to similar countries. But the important question remains: what are the economic and policy implications of being fifth, sixth or seventh in patent capture or production?

Economic Implications

It may seem that the AI tide will lift all boats. Indeed, most reports suggest that the greatest impact of AI, the increase in productivity, will be felt by all, from the Global South to the Global North.19 However, the greatest profit — as with other technological disruptions — is likely to be captured by the small number of corporations that own the technologies and an even smaller number of countries.20 This is because, while most AI companies are currently heavily unprofitable, if the forecasted productivity gains materialize, licensing profits would likely lead to profits comparable to present day software companies with similar models, such as Microsoft and Apple.

Headquarter location is key as, while these companies are some of the most prominent tax avoiders, historical evidence points to headquarter countries nevertheless capturing most of the tax revenue.21 This tax revenue becomes increasingly important because the productivity gains of AI are predicted to come at the cost of major job losses: approximately 300 million globally,22 or, for Canada, around 30 percent of the workforce.23 Therefore, owning the companies that profit most from the transition will be key to facilitating a sustainable transition, financing upskilling and compensating the ones most affected. Furthermore, beyond the direct revenue, strong evidence points to headquarters having important positive spillovers: headquarters attract headquarters.24 They also promote localized specialization, facilitating further innovation.25 Therefore, by forfeiting the creation of national players, Canada is swimming against the current. It forfeits the organic growth of industry and is forced to manually attract each company.

Policy Implications

Beyond the considerable economic implications of lagging behind in patent and technology ownership, there are the (arguably) more important consequences relating to sovereignty and the ability to regulate the technology’s development. The recent dispute between the Canadian26 (and Australian)27 government and American firms over news content on online platforms showcases a dilute version of the coming challenges. These companies have enormous control over the lives of Canadian citizens, and the intangible economy in which they operate allows services to cross borders, with little agency granted to governments to control them. While some jurisdictions have had more success in forcing compliance, in the end, the only government with certain control over them is in the country where they are headquartered. This is of particular importance for AI because the technology is set to have major impacts on the environment,28 the information space,29 human rights,30 and myriad other areas. If Canada wishes to guide the development of the technology, give value to its ethical guidelines, and grant any legitimacy to its decisions, it will first have to become a principal player in the field.

Canadian Policy

Canada has attempted, unsuccessfully, to close this gap, notably with the aforementioned 2017 Pan-Canada AI Strategy, updated in 2022. It remains in effect and has two main goals: increasing AI adoption; and increasing AI commercialization “at home.”31 To accomplish these goals, in partnership with the Quebec and Alberta governments the federal government has invested between C$15 million and 28 million per year since 2021.32 However, this strategy established no clear (publicly available) guidelines on who should receive this money and which organizations should be involved in the research. This has led to the “AI Institutes” tasked with utilizing these funds — Amii in Edmonton, Mila in Montreal, and the Vector Institute in Toronto — partnering heavily with foreign corporations.33 For example, Google is a Platinum Sponsor of the Vector Institute, as well as the former employer of the chief scientists at both Mila and Vector. Such a revolving door from a major foreign player has raised serious questions over the sovereignty of the strategy,34 to say nothing of the foundational and enduring partnerships and embedded research labs between these institutes, Google, Microsoft and Samsung.35 Given that these institutes do not publish funding metrics disaggregating public and private funds,iv Canadian funds and expertise may be shared with these companies which then — as the AI institutes act as bridges between researchers and industry — profit from them. This outcome is aligned with previous reporting on industry behaviour, which has highlighted that the model of Canadian AI seems to be to align the product with a major (foreign) AI player’s needs to optimize the odds of being acquired by them.36 This creates a vicious cycle where public investment goes to inventors who see themselves as feeders for foreign corporations. To this point, a major criticism of AI funding in Canada revolves around the lack of targeting and seemingly arbitrary distribution of funds.37 This is compounded by the lack of robust public impact or outcome assessment.38 While the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research (CIFAR) publishes yearly impact assessments for both the entire organization and the Pan-Canadian AI strategy, it shares very little information about the economic or societal impact of its investments. It prominently displays the importance of Canadian inventors — although comparing Canadian inventorship to the G7 which, as shown above, is a poor benchmark for economic benefit — and emphasizes the number of new research chairs and graduates, but makes no mention of patent ownership by Canadian firms or of the broader political and economic impacts of the inventions.39 The lack of priority given to outcomes, beyond producing inventors, may help explain the patent data showcased in this article.

In comparison, Korea has placed a clear emphasis on growing startups to a “global scale,” and on a “whole of economy” approach.40 It gives domestic startups priority access to funding and implicitly discourages foreign acquisitions.41 It develops “hybrid incubators” where the government, universities and corporations work hand-in-hand with startups to develop ecosystems.42 These choices have allowed the country to cultivate an industry that is outward looking, keeping track of international advancements and leveraging global knowledge networks, while protecting its inward interest, patriating profits and patents home. It also heavily contrasts with Canada’s arms-length and “fund it and forget it” approach. It fosters a modern ecosystem, aware that value is in rents, not wages. Canada’s new AI minister has promised to focus on protecting Canadian IP, commercialization and scaling up adoption.43 This rhetoric indicates awareness of the issue, but actions will have to follow.

Conclusion

Current rhetoric portrays AI innovation as a “race,”44 but the numbers point toward a game of chess. Positioning your players strategically appears much more important than being the fastest or smartest. China’s and South Korea’s performances show that by identifying key national players and dispersing them throughout the globe, even countries as small as Canada can become leaders in this field. The current Canadian strategy has enabled the country to increase its domestic invention capacity; however, if it wishes to revive its position as a global leader in the industry, and ensure a sustainable economic transition, it needs to reorient its innovation policy. At the time of writing, in late 2025, the Canadian government has begun a consultation to update its strategy.45 It may raise hope that Canada is willing to improve.

Appendix 1: AI Patent Search String, Orbit Intelligence

(((((ARTIFIC+ OR COMPUTATION+) 1W INTELLIGEN+) OR ((INDUCTIVE 1W LOGIC) 1D PROGRAMM+) OR ((NATURAL 1D LANGUAGE) 1W (GENERATION OR PROCESSING)) OR (ADABOOST) OR (BAYES+ 1W NETWORK+) OR (BAYESIAN_NETWORK) OR (BAYESIAN-NETWORK+) OR (BOOSTED 1W TREE+) OR (CHATBOT?) OR (CONNECTIONIS#) OR (DATA 1W MINING+) OR (DECISION 1W MODEL?) OR (DECISION TREE?) OR (DEEP 1W LEARN+) OR (DEEP 1W LEARNING+) OR (DEEP_LEARNING+) OR (DEEP-LEARNING+) OR (EXPERT 1W SYSTEM?) OR (FUZZY 1W LOGIC?) OR (GENETIC 1W ALGORITHM?) OR (GRADIENT TREE BOOSTING) OR (HIDDEN MARKOV MODEL?) OR (LATENT DIRICHLET ALLOCATION) OR (LATENT SEMANTIC ANALYSIS) OR (LEARNING 1W MODEL?) OR (LEARNING 3W ALGORITHM?) OR (LOGIC 1W MODEL+) OR (LOGIC 1W PROGRAM+) OR (LOGISTIC REGRESSION) OR (MACHINE 1W LEARN+) OR (MACHINE 1W LEARNING+) OR (MACHINE_LEARNING+) OR (MACHINE-LEARNING+) OR (MULTI-AGENT SYSTEM?) OR (MULTILAYER PERCEPTRON?) OR (NEURAL 1W NETWORK+) OR (NEURAL_NETWORK) OR (NEURAL_NETWORK+) OR (RANDOM FOREST?) OR (RANKBOOST) OR (REINFORCEMENT 1W LEARNING) OR (SEMI SUPERVISED 1W (LEARNING+ OR TRAINING)) OR (SEMI_SUPERVISED_LEARNING+) OR (SEMI-SUPERVISED-LEARNING) OR (STOCHASTIC GRADIENT DESCENT) OR (SUPERVISED 1W (LEARNING+ OR TRAINING)) OR (SUPERVISED_LEARNING+) OR (SUPERVISED-LEARNING+) OR (SUPPORT VECTOR MACHINE?) OR (SWARM 1W INTELLIGEN+) OR (SWARM_INTELLIGEN+) OR (SWARM-INTELLIGEN+) OR (TRANSFER 1W LEARNING) OR (TRANSFER_LEARNING) OR (TRANSFER-LEARNING) OR (UNSUPERVISED 1W (LEARNING+ OR TRAINING)) OR (UNSUPERVISED_LEARNING+) OR (UNSUPERVISED-LEARNING+) OR (XGBOOST))/TI/AB/CLMS/DESC/ODES/OBJ/ADB/ICLM OR ((A61B-005/7264) OR (A61B-005/7267) OR (A61B-005/7267) OR (A61B-005/7264:A61B-005/7267) OR (A63F-013/67) OR (B23K-031/006) OR (B23K-031/006) OR (B25J-009/161) OR (B29C-2945/76979) OR (B29C-2945/76983) OR (B29C-066/965) OR (B29C-066/966) OR (B29C-066/965) OR (B60G-2600/1876) OR (B60G-2600/1878) OR (B60G-2600/1879) OR (B60G-2600/1876) OR (B60G-2600/1878) OR (B60G-2600/1879) OR (B60W-030/06) OR (B60W-030/10:B60W-030/12) OR (B60W-030/14:B60W-030/17) OR (B62D-015/0285) OR (B64G-2001/247) OR (B64G-2001/247) OR (E21B-2041/0028) OR (E21B-2041/0028) OR (F02D-041/1405) OR (F02D-041/1405) OR (F03D-007/046) OR (F05B-2270/707) OR (F05B-2270/709) OR (F05B-2270/709) OR (F05D-2270/709) OR (F16H-2061/0081) OR (F16H-2061/0084) OR (F16H-2061/0081) OR (F16H-2061/0084) OR (G01N-2201/1296) OR (G01N-029/4481) OR (G01N-033/0034) OR (G01N-029/4481) OR (G01N-033/0034) OR (G01N-2201/1296) OR (G01R 031/2846:G01R-031/2848) OR (G01R-031/3651) OR (G01S-007/417) OR (G01S-007/417) OR (G05B-013/0275) OR (G05B-013/027) OR (G05B-013/0275) OR (G05B-013/028) OR (G05B-013/0285) OR (G05B-013/029) OR (G05B-013/0295) OR (G05B-2219/33002) OR (G05B-013/027) OR (G05B-013/028) OR (G05B-013/0285) OR (G05B-013/029) OR (G05B-013/0295) OR (G05B-2219/33002) OR (G05D-001/0088) OR (G05D-001) OR (G05D-001/0088) OR (G06F-011/1476) OR (G06F-011/1476) OR (G06F-011/2263) OR (G06F-2207/4824) OR (G06F-030/27) OR (G06F-011/2257) OR (G06F-011/2263) OR (G06F-015/18) OR (G06F-017/16) OR (G06F-017/2282) OR (G06F-017/27:G06F-017/2795) OR (G06F-017/28:G06F-017/289) OR (G06F-017/30029:G06F-017/30035) OR (G06F-017/30247:G06F-017/30262) OR (G06F-017/30401) OR (G06F-017/3043) OR (G06F-017/30522:G06F-017/3053) OR (G06F-017/30654) OR (G06F-017/30663) OR (G06F-017/30666) OR (G06F-017/30669) OR (G06F-017/30672) OR (G06F-017/30684) OR (G06F-017/30687) OR (G06F-017/3069) OR (G06F-017/30702) OR (G06F-017/30705:G06F-017/30713) OR (G06F-017/30731:G06F-017/30737) OR (G06F-017/30743:G06F-017/30746) OR (G06F-017/30784:G06F-017/30814) OR (G06F-019/24) OR (G06F-019/707) OR (G06F-2207/4824) OR (G06K-007/1482) OR (G06K-007/1482) OR (G06K-009) OR (G06N 007/005:G06N-007/06) OR (G06N-020) OR (G06N 3/02-126) OR (G06N-005) OR (G06N 7/00-06) OR (G06N-003) OR (G06N-003/004:G06N-003/008) OR (G06N-005/003:G06N-005/027) OR (G06N-007/046) OR (G06N-099/005) OR (G06T-2207/20081) OR (G06T-2207/20084) OR (G06T-003/4046) OR (G06T-009/002) OR (G06T-003/4046) OR (G06T-009/002) OR (G06T-2207/20081) OR (G06T-2207/20084) OR (G06T-2207/20084) OR (G06T-2207/30236) OR (G06T-2207/30248:G06T-2207/30268) OR (G08B-029/186) OR (G08B-029/186) OR (G10H-2250/151) OR (G10H-2250/311) OR (G10H-2250/151) OR (G10H-2250/311) OR (G10K-2210/3024) OR (G10K-2210/3038) OR (G10K-2210/3024) OR (G10K-2210/3038) OR (G10L-015/16) OR (G10L-017/18) OR (G10L-025/30) OR (G10L-015) OR (G10L-017) OR (G10L-025/30) OR (G11B-020/10518) OR (G11B-020/10518) OR (H01J-2237/30427) OR (H01J-2237/30427) OR (H01M-008/04992) OR (H01M-008/04992) OR (H02H-001/0092) OR (H02P-021/001) OR (H02P-021/0014) OR (H02P-023/0013) OR (H02P-023/0018) OR (H02P-021/0014) OR (H02P-023/0018) OR (H03H-2017/0208) OR (H03H-2222/04) OR (H03H-2017/0208) OR (H04L-025/0254) OR (H04L-2012/5686) OR (H04L-2025/03464) OR (H04L-2025/03554) OR (H04L-025/0254) OR (H04L-025/03165) OR (H04L-041/16) OR (H04L-045/08) OR (H04L-025/03165) OR (H04L-041/16) OR (H04L-045/08) OR (H04L-2012/5686) OR (H04L-2025/03464) OR (H04L-2025/03554) OR (H04N 021/4662:H04N-021/4666) OR (H04N-021/4662) OR (H04N-021/4663) OR (H04N-021/4665) OR (H04N-021/4666) OR (H04N-021/4666) OR (H04Q-2213/054) OR (H04Q-2213/13343) OR (H04Q-2213/343) OR (H04Q-2213/054) OR (H04Q-2213/13343) OR (H04Q-2213/343) OR (H04R-025/507) OR (H04R-025/507) OR (Y10S-128/924) OR (Y10S-128/925) OR (Y10S-706) OR (Y10S-128/924) OR (Y10S-128/925) OR (Y10S-706))/IPC/CPC) AND (APD=2005-01-01:2023-12-31))

Appendix 2: Patent Ownership Adjustments as a Percentage of Total Patents, by country, 2005–2023

| Year | Canada | China | EU-27 | Great Britain | Japan | United States | Korea |

| 2005 | -12.12% | -4.02% | -71.89% | -0.88% | 0.00% | 1.07% | -0.31% |

| 2006 | -5.41% | -8.41% | -65.75% | -0.88% | 0.00% | 1.25% | -0.26% |

| 2007 | -8.96% | -8.82% | -62.71% | -0.98% | 0.00% | 1.02% | -0.40% |

| 2008 | -9.83% | -8.67% | -73.68% | -1.57% | 0.00% | 1.40% | -0.50% |

| 2009 | -11.21% | -12.40% | -78.55% | -0.77% | 0.00% | 1.55% | -0.64% |

| 2010 | -7.93% | -8.59% | -71.62% | -1.25% | 0.00% | 1.14% | -0.48% |

| 2011 | -6.62% | -10.83% | -62.71% | -1.04% | 0.00% | 1.46% | -0.39% |

| 2012 | -4.78% | -6.24% | -60.91% | -1.18% | 0.00% | 1.68% | -0.19% |

| 2013 | -4.51% | -6.96% | -52.45% | -1.14% | 0.00% | 1.40% | -0.20% |

| 2014 | -4.27% | -4.51% | -38.36% | -1.05% | 0.00% | 0.84% | -0.29% |

| 2015 | -6.17% | -2.20% | -31.37% | -0.89% | 0.00% | 1.00% | -0.30% |

| 2016 | -11.37% | -0.79% | -34.14% | -0.95% | 0.00% | 1.24% | -0.23% |

| 2017 | -13.63% | -0.43% | -39.66% | -0.73% | 0.00% | 1.01% | -0.30% |

| 2018 | -13.33% | 0.01% | -37.70% | -0.65% | 0.00% | 0.56% | -0.08% |

| 2019 | -16.07% | 0.02% | -27.43% | -1.07% | 0.00% | 0.32% | -0.08% |

| 2020 | -14.76% | 0.59% | -30.16% | -0.91% | 0.00% | -1.51% | 0.00% |

| 2021 | -16.26% | 0.62% | -32.99% | -0.97% | 0.00% | -1.99% | 0.00% |

| 2022 | -15.17% | 0.46% | -35.73% | -1.13% | 0.00% | -1.05% | 0.00% |

| 2023 | -18.74% | 0.25% | -32.37% | -1.31% | 0.00% | -0.23% | 0.00% |